This essay continues the Christian Theology and Public Policy Course by John Cobin, author of the books Bible and Government and Christian Theology of Public Policy. It is the second installment of a seven part series dealing with Christians and rebellion against the civil authority, originally titled “Christian Views on Rebellion.”

—-

The Bible indicates that being a revolutionary can bring temporal trouble. “My son, fear the Lord and the king; do not associate with those given to change [via revolution]; for their calamity will rise suddenly, and who knows the ruin those two can bring?” (Proverbs 24:21-22). When the Jewish religious leaders were “furious” with the Apostles for preaching the Gospel, Gamaliel reminded his Council about the failed revolutionary attempts of Theudas and Judas of Galilee (and their men)—most of whom were executed by the civil authorities (Acts 5:33-39). Not all revolutionary attempts fail of course, but the probability of success is low and the likelihood of imprisonment or death for treason is high. As Gamaliel said, if a revolutionary movement “is of God” it will stand; otherwise it will fail. And the general counsel of the Bible is that if one wants to preserve his life he had better think twice about being a revolutionary.

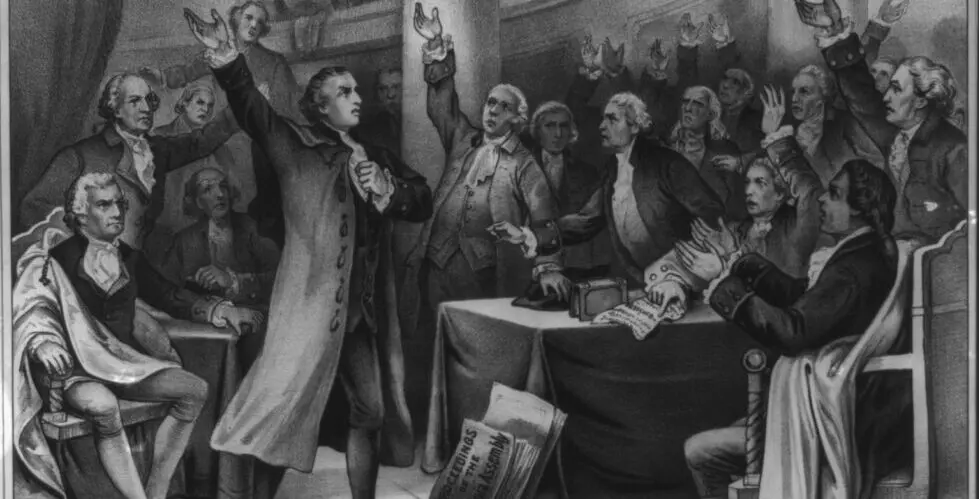

The Founding Fathers knew what they were getting into in opposing the world’s most powerful empire. Their commitment was summed up in the closing language of the Declaration of Independence: “And for the support of this Declaration with a firm reliance on the protection of divine providence, we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.” The Founders who read Proverbs 24:21 evidently viewed it as mere practical advice about avoiding temporal consequences rather than as a general directive to be obeyed in all cases. And their resulting successful revolt was extraordinary, being aided by many symbiotic cultural dynamics of the time. Still, Proverbs 24:21-22 and Acts 5:33-39 provide a constant reminder to Christians to beware of participating in revolution. Indeed, what was practical for the Founders might not be prudent for us today. Moreover, the Bible indicates that the motive for submitting to civil authority is to glorify God, to avoid worldly distractions that detract from the church’s main mission, and that Christians may lead “a quiet and peaceable life” (1 Timothy 2:2). At least in the short term, revolution would seem to be counter-productive to evangelism and building the church.

In order to meet such biblical objectives, Christians may have to be practical or expedient when confronted by the civil authority. The Bible counsels that when eating with a ruler, “put a knife to your throat if you are a man given to appetite” (Proverbs 23:2). Jesus told Peter to fetch a coin from the mouth of a fish—not because he had been worried about His unpaid tax liability but because He did not want to “offend” the civil authorities (Matthew 17:27). Jesus knew that the tax had not been paid and yet had apparently expressed no concern about breaking the rules. Perhaps this event formed part of the rationale that led the Pharisees to accuse Jesus of “forbidding to pay taxes to Caesar” (Luke 23:2). At any rate, avoiding confrontation in general is important for a Christian. This ideal is the driving force behind the Apostle Peter’s wide admonition: “Honor all people. Love the brotherhood. Fear God. Honor the king” (1 Peter 2:17). The American Founders sought to avoid confrontation with King George III, and only after what Thomas Jefferson called a “long train of abuses and usurpations” did they choose to “rebel” against him. Would the Apostles have rebelled against Rome at some point too? Surely, Nero was every bit as evil and defiant as King George III, and yet the Apostles did not rebel against Nero. Perhaps they would have done so—at least if they had the arms and soldiers to pull it off (cf. Luke 14:31). The War for American Independence was fought over a fundamental issue of authority: specifically, the place where “the consent of the governed” rested and who was entitled to rule. In 1775, there was widespread doubt about the legitimacy of centralized power exercised from London.

Apparently the Christians in the 1770s believed that civil disobedience and armed revolution were justified and prudent so long as a good or godly reason could be found for such revolt and as long as the insurgents were backed with sufficient firepower to have a decent shot at success. The Scripture is silent (or at least not conclusive) on whether Christians can revolt against the state when they have the means to do so. We do not know what Paul and Peter would have done or taught if pro-Christian forces were able to muster sufficient resources to defy Nero. Yet the Scriptures seem to indicate that Christians have a right of self-defense (Luke 22:36), which could be taken as the right of defense against both criminals and state plunderers like King George III—or George W. Bush for that matter. Or should we simply believe that apostolic teaching regarding submission to (and honoring of) civil rulers prohibits Christians from ever defending themselves against them? Must Christians never attack civil rulers—no matter how tyrannical the state becomes or how much it plunders its citizenry? I don’t think so.

The Tory preacher’s view, “Rebellion against authority is rebellion against God”, is wrong while the Founders’ actions were right. King George III was an overbearing thief and a depriver of civil liberties. Since the colonists had the power to resist, they were rightly exhorted to do so—especially considering the implications of 1 Corinthians 7:21-24. For some of us, no further justification is needed to attack a wayward, tyrannical, and predatory state beyond the fact that is plundering us or depriving us of our liberties. Like a robber or other criminal, the state can be opposed when it is prudent and possible to do so.

Other willing Christian insurgents, however, need further validation. For instance, many preachers and theologians in the 1770s proclaimed that Romans 13:1-7 and 1 Peter 2:13-17 were only binding insofar as government honors its “moral and religious” obligations. Otherwise, the duty of submission was nullified. Indeed, rulers had no authority from God to do mischief; it was blasphemous to call tyrants and oppressors the ministers of God. And each individual was left to decide when a ruler crossed the line. In the final analysis, using either of these methods to justify civil disobedience leads to the conclusion that state tyranny can be properly resisted by Christians. Indeed, Christians are remiss who do not oppose tyrants.

—-

Originally published in The Times Examiner on March 30, 2005.

Articles posted on LCI represent a broad range of views from authors who identify as both Christian and libertarian. Of course, not everyone will agree with every article, and not every article represents an official position from LCI. Please direct any inquiries regarding the specifics of the article to the author.

Did you read this in a non-English version? We would be grateful for your feedback on our auto-translation software.

), //libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

), https://libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

), https://libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

), https://libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

), https://libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

*by signing up, you also agree to get weekly updates to our newsletter

Sign up and receive updates any day we publish a new article or podcast episode!