And ye shall cry out in that day because of your king which ye shall have chosen you; and the LORD will not hear you in that day. Nevertheless the people refused to obey the voice of Samuel; and they said, Nay; but we will have a king over us; that we also may be like all the nations; and that our king may judge us, and go out before us, and fight our battles.

1 Samuel 8:18–20

We celebrate Independence Day in the United States on July 4th to commemorate American colonies rejecting the British monarchy. That is the day when the Continental Congress announced a plan for American self-government. As Christians thinking about this historical event in America and its meaning, it is instructive to look at the time when Ancient Israel adopted its monarchy.

Why American independence?

The American secessionists mostly considered themselves Englishmen, and legally they were Englishmen. The English monarch of the day, King George III (b. June 1738, d. Jan 1820), was king of the United Kingdom and held titles in the Holy Roman Empire as the third English king from the House of Hanover.

George III was the longest-reigning king in English history up to that point. He assumed the throne at age 22 and reigned for 59 years until his death. He was one of the most war-mongering kings in English history. He oversaw the conclusion of the Seven Years’ War (1763), making Britain the dominant power in North America and India. He fought to maintain his American possessions in the American War for Independence (1775–1783). He also waged wars against France during his reign.

Mental illness began to invade his life after the death of two sons at the end of the American war. Historians have speculated about the cause of his mental health decline. Theories range from a possible genetic condition to accidental arsenic poisoning from his cosmetics. He was seen to be deranged, foaming at the mouth, and endlessly babbling until he became hoarse. He supposedly spoke to a tree as if it were the King of Prussia. He had to be forcibly restrained by his doctors at times.

In 1789, the House of Commons acted to give power to the Prince of Wales while the king was suffering an extended episode. However, the king recovered, and the House of Lords didn’t take it up. For the last decade of his life, he was blind from cataracts, mostly deaf, and suffering from delusions and dementia. His political authority was taken away for the last nine years of his life, as he lived in seclusion as a lunatic in Windsor Castle.

In 1776, a year into American conflict, the Declaration of Independence included a list of numerous grievances against the King and his government.

- He would not allow colonies to freely pass their own laws.

- When colonial governors tried to get his approval, the king never got around to it.

- The king was getting colonies to relinquish their parliamentary representation in exchange for other favorable treatment.

- His government set difficult procedural requirements that made local government impracticable (time, location, etc.).

- He dissolved government bodies that resisted him; wouldn’t allow them to be replaced.

- He blocked people’s free travel to the colonies, and their ability to homestead more land.

- He failed to provide for a court system.

- Judges were basically just automatons of the king.

- “Swarms” of new government officials were sent to “harass our people and eat out their substance.”

- Standing armies were kept among the people, with local civil authorities in subjection to the military.

- His policies of military/royal rule over colonialists were unconstitutional under the unwritten English constitution contained in the body of common law court decisions.

- He was quartering many troops in homes.

- There were no consequences for troops who engaged in criminal conduct.

- The king was cutting off international trade.

- There was taxation without consent.

- The right to trial by jury was not being honored.

- Trials in faraway courts were conducted for “pretended offenses.”

- The withdrawal of the English system of rights in neighboring colonies, and revolutionaries were worried they were next.

- There was no consistency in how local governments were being recognized/treated.

- The royal government was arbitrarily shutting down state legislatures.

- The king was failing to physically protect the colonies.

- He actively harmed the colonies, burned towns, and killed people.

- He was sending mercenaries to kill more people and institute further tyranny and barbarism.

- The British navy was conscripting American sailors.

- The king’s government was stirring up domestic trouble with neighbors, Indians, and others.

Citing repeated attempts to get the king to do right, the Declaration was signed by men who said they were “appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions.” Political independence means rejecting rule by an outside power and choosing self-rule under God.

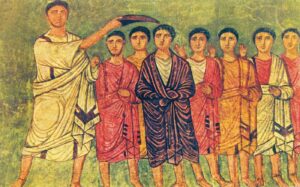

Israel’s counter-revolution

In the Old Testament, from the time of Abraham until the time of Moses, civil authority was vested in local elders, in a sort of tribal, or extended family-based government. Sometimes, the ancient Hebrews were subjected to local jurisdictions and rulers of other nations. Most famously, the Israelites were subjected to bondage in Egypt, ultimately escaping Egyptian servitude under the leadership of Moses.

From the time of Moses and Aaron until Samuel, civil authority in Israel was distributed across trusted elders (Ex. 18:17–23). In addition to their sacrificial and other temple responsibilities, final authority over legal disputes rested with priests. Periodically, God raised a judge to deliver and guide Israel, but these judges were not to become monarchs.

After God’s great victory for Israel against the Midianites, Gideon had refused rule when the Israelites offered to grant him a hereditary monarchy. (Judges 8:22–23). Sadly, his son by a concubine, Abimelech, had no such compunction against taking power.

After Gideon’s death, Abimelech later convinced men at Shechem to make him their ruler. He killed seventy of his brothers, with only the youngest, Jotham, escaping the massacre. After three years of rule, Abimelech was mortally wounded by a woman who dropped a millstone on his head at Thebez. In his pride, he commanded his male servant to kill him so that he would not be vanquished at the hand of a woman.

The next time the Israelites sought a king was recorded in 1 Samuel 8. This time, it was the “elders of Israel” who approached Samuel to ask for a king. The Hebrew word zä·kān’ is translated here as “elder.” The word can be used to refer to old people or to an elder in the sense of one in a position of authority. Here, rendered as “elders of Israel,” the word is clearly referring to those in local authority. In English, we might talk about “senior people in the organization.” The word “senior” comes from a Latin word meaning “old.” These uses are based on the same idea, that age naturally confers authority.

The first reason that the elders gave for their demand for a king was based on a sort of “good government” claim. Samuel’s sons, Joel and Abiah, were distracted by wealth, and they were taking bribes and perverting justice (v. 3). Samuel was a good, honest judge (vv. 3–4). The elders were raising a legitimate, conscientious concern based in God’s law.

For example, in Deuteronomy 16:19, scripture says “You shall not distort justice; you shall not be partial, and you shall not take a bribe, for a bribe blinds the eyes of the wise and perverts the words of the righteous.” Qualifications for those judging disputes were described in Exodus 18:21–22 and included: competence, a righteous fear for God, trustworthiness, outright hate for dishonest gain, and humility.

Samuel was greatly troubled by their words. One can imagine that as a father, hearing serious attacks on his sons’ moral character would have been discouraging. As God’s priest and prophet, though, Samuel also had to be concerned about whether the elders were requesting something that honored God. Samuel went to God in prayer.

God instructed Samuel to listen to the elders. God also told Samuel that by demanding a king, the elders are not just rejecting Samuel’s authority. They are rejecting the authority of God Himself to rule Israel.

God delivered Israel out of Egypt and had been faithful to His people, but they had forsaken Him and turned to false gods. Now Israel’s rejection of Samuel is another demonstration of the same thing: a lack of faith in the one true God. The elders were not wrong to be concerned about the bad acts of Samuel’s sons. However, they should have relied on God to provide, just as He had provided Samuel when Eli before him had raised sons who corrupted the tabernacle. Instead, the elders wanted to put their faith in a human ruler.

God’s direction to Samuel was simple: tell them all the horrible things a king will do to them (v. 9). He would take their sons for himself, his chariots, his horsemen, and to run before his chariots (v. 11). Government officials would take over affairs great and small, controlling agriculture and industry for the benefit of the king(v. 12).

The king would take their daughters to prepare his food (v. 13), take the best land to give to the people working for him (v. 14), and take a tenth of seed and from vineyards to pay his officers and servants (v. 15). The king would take all the best workers and use them for what he wants instead (v. 16), and he would take a tenth of their livestock (v. 17a). (“Sheep” in some translations; trans. from tso’n, from a root word meaning “to migrate”; the reference here is to multitudes of small cattle, livestock in flocks or herds including sheep and goats.) A king would make the people his servants (v. 17b). Under the king they were going to get, Israel would cry out to God for help and would not get it. (v. 18)

Samuel takes this burdensome message back to the elders. He tells the people all these things that will befall them if they crown a king. Far from good government, crowning a king will subject them to far worse injustice.

But Israel’s elders demanded a king anyway (v. 19). Undeterred by Samuel’s warning from God, they revealed a second reason for demanding a king: “[to] judge us, and go out before us, and fight our battles.” (v. 20)

The people wanted a warlord to lead them into battle like the neighboring nations had. This is a sad decline in faith from only a chapter earlier, when Israel notably trusted in God for victory over the Philistines. (1 Sam. 7:8) Now, they wanted to put their trust in a human champion instead of the God of Abraham and Isaac and Moses.

With the call for a king unrelenting, Samuel again prays. “Samuel rehearsed all their words in the ears of the Lord.” (1 Sam. 8:21). God instructs Samuel to give them a king, and Samuel sends everyone home (v. 22).

Saul was a Benjamite. Benjamin was a much-diminished tribe after the war with Gibeah. This meant that the tribal inheritance was spread across a smaller number of men. Saul’s father, Kish, was wealthy and powerful (1 Sam. 9:1). Saul was as handsome as any man in Israel, and he was exceptionally tall (v. 2).

He enters the scene in scripture while he is looking for his father’s donkeys (v. 3), which he had lost earlier (v. 20). Initially, Saul seems genuinely willing to accept the Lord’s leading, anointment, and counsel from Samuel. We see, for example, the episode of Saul among the prophets (v. 11).

Saul was also what the people wanted in one important sense: he was a military man. He led military campaigns in Jabesh-Gilead against the Ammonites. Then there were more conflicts with Moabites, Ammonites, Edomites, the kings of Zobah, Philistines, and Amalekites. Like Samuel’s sons, his eye was eventually turned by wealth. Incomplete obedience in the war against Amalekites led to Saul keeping the king and the best livestock alive (1 Samuel 15).

Saul was finally rejected by God as Israel’s ruler, and David entered the scene. David was an imperfect king, too, but an ancestor of Joseph and of Mary. He was an important ancestor in a royal line down to the Lion of Judah, the real solution to all the world’s problems.

Trusting the right king

King George and Saul both came from respected families. Both men were well-loved by those whom they ruled — at least at times. People in more modern times, like those in the ancient world, are attracted by the promise of a human leader who can champion their cause and win their fights for them.

As Christians, we should trust in God, not in men, and not in chariots and horses (Psalm 20:7). It is spiritual treason to put faith in men for what we should look to God to provide — God is sovereign! As we observe celebrations surrounding Independence Day, we should seek the independence that comes from only one thing: trusting Christ fully.

), //libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

), https://libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

;?>/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/sqb-registration-img.jpg)