“Am I not allowed to do what I choose with what belongs to me?” —Matthew 20:15

Do businesses exist to serve shareholders? Or do they exist to serve the interests of all stakeholders, including communities and the environment?

Milton Friedman’s doctrine of shareholder primacy has been much maligned, mischaracterized, and misunderstood over the past several decades. Unfortunately, Friedman himself may be partially to blame for this because of his emphasis on profit-seeking rather than fulfilling the desires and goals of shareholders. In his seminal New York Times essay, Friedman argues that “the social responsibility of business is to increase profits.” For decades, this way of thinking swayed many economists and capital owners alike into believing that profit maximization is the chief or even the only legitimate goal of business.

It blended in the cultural psyche with Hollywood’s Gordon Gecko philosophy that “greed is good” and eventually came to be thought of (mainly by the doctrine’s opponents) as espousing “profits at all costs” or “profits over people.” This version of capitalism is blamed for everything from corporate short-termism to leveraged buyouts to the 2008 financial crisis. But is it really what Friedman endorsed?

It’s true that Friedman didn’t mince words about those who wanted to expand the proper role of business:

The businessmen believe that they are defending free enterprise when they declaim that business is not concerned “merely” with profit but also with promoting desirable “social” ends; that business has a “social conscience” and takes seriously its responsibilities for providing employment, eliminating discrimination, avoiding pollution and whatever else may be the catchwords of the contemporary crop of reformers.

Friedman calls this way of thinking “pure and unadulterated socialism.”

But the Chicago School economist was no acolyte of Ayn Rand’s moral philosophy. He didn’t espouse the morality of selfishness—either Rand’s rational self-interest or Gordon Gecko’s greed. In fact, Friedman advocated private charity as an important ally of the free market. It was no accident, in his view, that the 19th century experienced both the freest economy and “the greatest private eleemosynary [charitable] activity in the history of the United States.”

Friedman simply thought that this philanthropic activity fell outside the purview of business activity. “What does it mean to say that ‘business’ has responsibilities? Only people can have responsibilities.” That is, only people have moral responsibilities toward each other. Corporate structures dictate responsibilities between shareholders (or owners) and managers (or executives). But Friedman also acknowledged that not all shareholders/owners held profit maximization as the sole or primary goal of the enterprise:

In a free‐enterprise, private‐property system, a corporate executive is an employee of the owners of the business. He has direct responsibility to his employers. That responsibility is to conduct the business in accordance with their desires, which generally will be to make as much money as possible while conforming to the basic rules of the society, both those embodied in law and those embodied in ethical custom. Of course, in some cases his employers may have a different objective.

…In either case, the key point is that, in his capacity as a corporate executive, the manager is the agent of the individuals who own the corporation or establish the eleemosynary [charitable] institution, and his primary responsibility is to them.

In other words, most of the time, business owners hire managers to run their companies for maximum profits—while operating within the parameters of the law and ethical standards, of course. (This already goes against the portrayal of shareholder primacy as pushing for profits even over and against the law and ethics.) But, in many cases, business owners desire more than just profits. Sometimes they want to pay their employees above-market wages, or donate to philanthropic or community development causes, or pursue certain projects that would be less profitable than others for environmental or humanitarian reasons. In these cases, the duty of managers/executives is to operate the business the way the shareholders/owners desire it to be operated.

That is what shareholder primacy really means. Not “profits at all costs” or “profits over people.” Unfortunately, the framing of this theory as asserting that “the social responsibility of business is to increase profits” has led to myriad mischaracterizations over the years. Marc Benioff, CEO of Salesforce, provides one such example when he describes his view on the theory in a recent New York Times piece:

I didn’t agree with Friedman then, and the decades since have only exposed his myopia. Just look where the obsession with maximizing profits for shareholders has brought us: terrible economic, racial and health inequalities; the catastrophe of climate change.

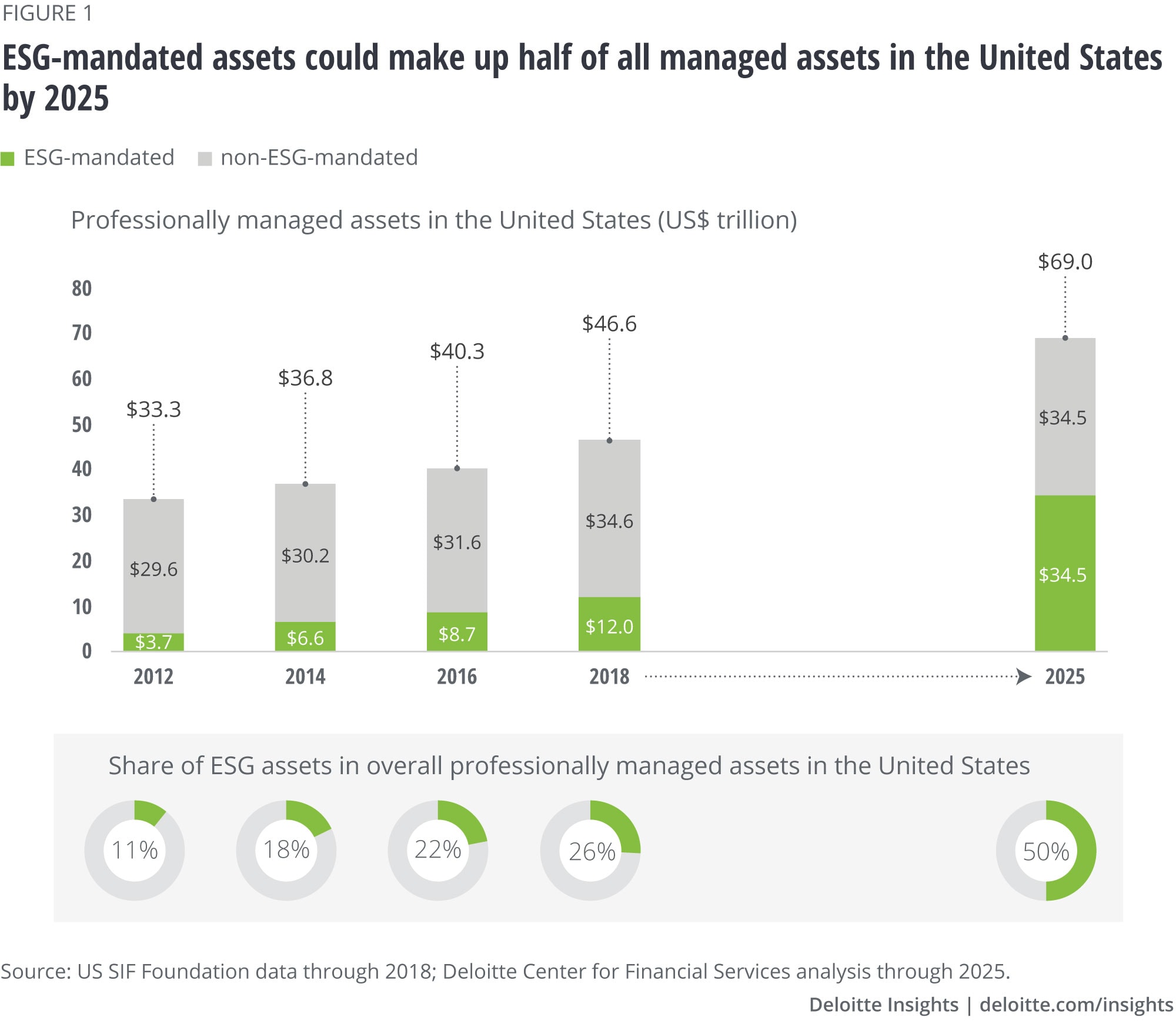

The irony is that there has been a massive, voluntary push by none other than investors—i.e. shareholders/business owners—toward what’s called “socially responsible investing” in recent years. Hundreds of billions of dollars have flooded into ESG (“environmental, social, governance”) funds in the last five years or so, and by some projections half of all institutionally managed assets could be in ESG-mandated funds by 2025.

Earlier this year, Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan told CNBC that “[a]ll investors are saying, ‘I want you to invest in companies doing right by society.’” The firm held $25 billion in ESG funds in January, and that number is growing. The largest institutional investment management firms—Vanguard, BlackRock, Fidelity, Charles Schwab, Invesco, etc.—have all led the charge toward this new “environmentally and socially responsible” investment world, and they’ve done it in response to demand from investors.

The major alternative to shareholder primacy is called “stakeholder theory,” which has surged in popularity recently. The theory asserts that owners or shareholders do not (or should not) have full control of their companies but rather (should) share control with other stakeholders such as employees, customers, vendors, communities, and the environment. Some proponents of stakeholder theory are of the view that this should be a voluntary decision made by owners/shareholders, while others assert that it should be the law of the land, enforced by the government.

In reality, the voluntary preference of business owners to share decision-making powers with other stakeholders is not at all incompatible with shareholder primacy. Only the legally enforced version of stakeholder theory is incompatible with Friedman’s thinking. For the most part, “stakeholder capitalism” is not currently enforced by government mandate (unless you count such laws as the minimum wage, environmental regulations, anti-discrimination rules, etc.).

If Marc Benioff, as CEO of Salesforce, decided to manage in a way that went against the wishes of shareholders, even if it benefited all the other stakeholders, he could still get the boot and the government could do nothing about it. But the truth is that shareholders, for the most part, love the way he manages. They love that Salesforce has a “Chief Equality Officer,” a “Chief Impact Officer,” and a “Chief People Officer.” They love the company’s focus on social impact and mitigating climate change. If they didn’t, shareholders—through their appointed representatives on the Board of Directors—would tell him to clear his desk and start looking for a new job.

Maybe others will look at the way the shareholders/owners choose to run Salesforce and feel shock, disgust, or mere disagreement. Maybe they would run the company a different way. But that is the nature of capitalism—namely, shareholder capitalism. Business owners have the right to run their enterprises how they see fit.

I believe that, as Christians, this is something to be celebrated. I know a Christian business owner who gives 20% of his company’s profits to gospel-focused charitable causes every year. It motivates him to work hard and generate more income so as to give away an increasing amount over time. The entire “business as mission” movement could not exist if Benioff’s distorted mischaracterization of shareholder primacy was true. The book Great Commission Companies: The Emerging Role of Business in Missions documents many of these Christian businesses blending profit-seeking with Kingdom-building. And, in fact, there is also a burgeoning “Biblically responsible investing” trend that is capturing millions of believers’ dollars.

Though I may not like the framing or emphasis of the essay, the key point that Milton Friedman raised is as true today as it was in 1970: corporate executives are employees of the business’s shareholders/owners and should abide by their wishes, within the parameters of the law. That does not mean that shareholders always desire profit maximization above all else. Quite the contrary, as the ESG and “business as mission” movements prove.

Unfortunately, business leaders and media members seem to be invested in the popular mischaracterization of Friedman’s theory. Perhaps they calculate that to try to set the record straight would come across as defending the undefendable—profit maximization above all else. The paradoxical truth is that, by decrying Friedman and spouting “the catchwords of the contemporary crop of reformers,” most of them are actually engaged in an attempt to please their shareholders.

Articles posted on LCI represent a broad range of views from authors who identify as both Christian and libertarian. Of course, not everyone will agree with every article, and not every article represents an official position from LCI. Please direct any inquiries regarding the specifics of the article to the author.

Did you read this in a non-English version? We would be grateful for your feedback on our auto-translation software.

), //libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

), https://libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

), https://libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

), https://libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

), https://libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

*by signing up, you also agree to get weekly updates to our newsletter

Sign up and receive updates any day we publish a new article or podcast episode!