“You hypocrite, first take the plank out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to remove the speck from your brother’s eye.” — Matthew 7:5

I grew up going to numerous youth group events, Christian summer camps, weekly chapels at my Christian high school, and of course church services once a week (or more). A common theme of so many evangelical speakers in my youth was the importance of integrity. It is the concept that you do what you do and behave the way you behave because it is who you are. It is your character. It is how you would act whether your peers see you or not. “Behind closed doors” was a phrase I heard often. If you act differently behind closed doors, when your Christian peers (or family, pastor, etc.) can’t see you, you lack integrity.

If you act one way on Sunday and another way the rest of the week, then you are a person of low integrity.

Another way of thinking about it is whether one’s behavior and thinking and principles are the same regardless of whether it personally benefits them or not. Standing firm on the right thing when it benefits you doesn’t necessarily reveal integrity. It’s when you continue to stand firm on it—unwaveringly—despite that stance being detrimental to your personal self-interest that your behavior demonstrates true integrity.

I also grew up and came of age in an evangelical culture that feared and loathed the ever-mounting national debt, seeing it mostly as a result of liberal largesse—never the fault of conservative Republicans, of course. (Never mind the continual push for more and more military spending. That’s necessary, and totally worth going into deeper debt.)

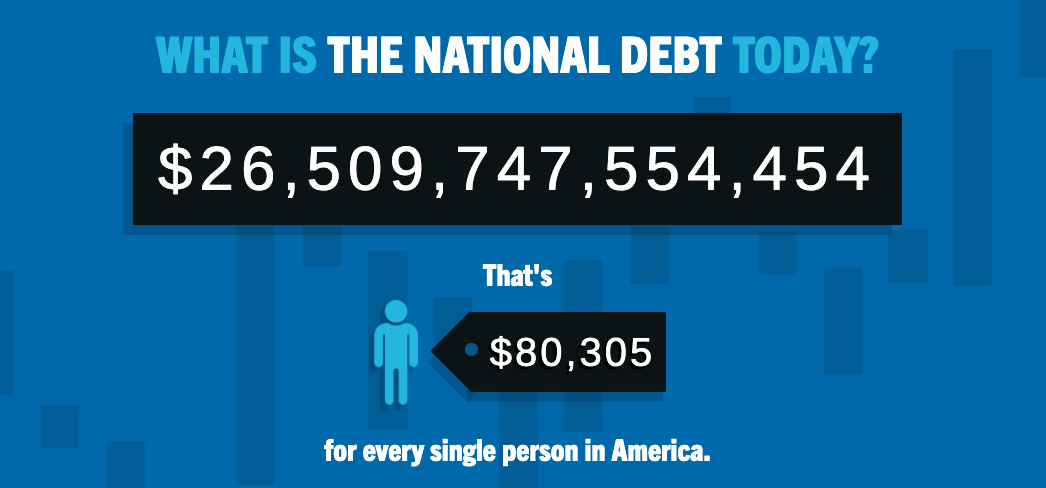

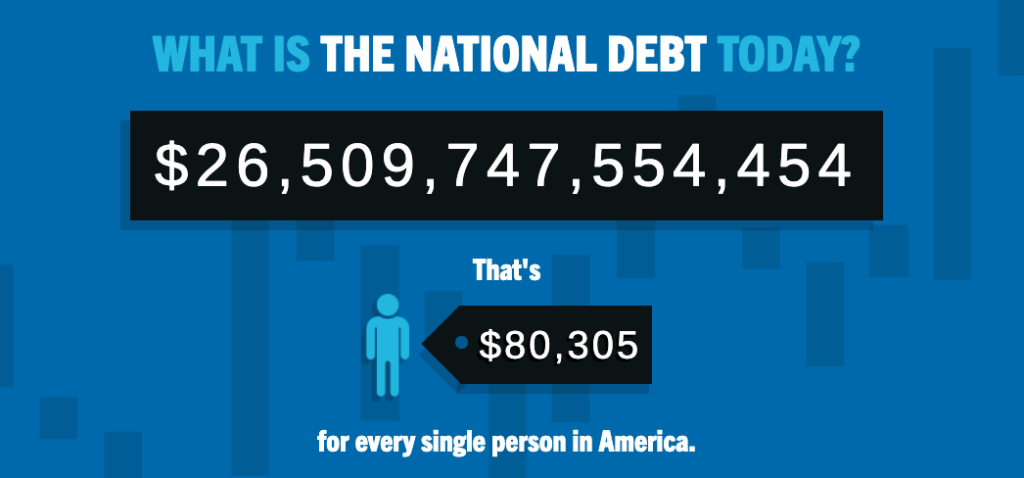

Back in 2011, in the middle of Barack Obama’s first presidential term, it was all the rage in conservative Christian circles to talk about not just the danger but also the immorality of the debt. As Obama’s 2012 budget was being debated, evangelical leaders warned against the immoral proportions that the $14 trillion national debt had reached. (Oh, that it could still be a trifling $14 trillion!) I still remember the genuine anxiety, the head-shaking, the “can-you-believe-this?”-type questions exchanged between adults.

Evangelical leaders stoked this unease. “America’s growing debt is a not just a financial issue, it’s a spiritual one,” said Jerry Newcombe, host of a Christian TV program, “The Bible is very clear about the moral dangers of debt.” Historian and author William Federer, a guest on Newcombe’s program, added, “Proverbs 13:22 says a ‘good man leaves an inheritance for his children’s children.’ Right now, we’re not leaving a very good inheritance.”

Back then, I was entering my third year of college and largely apathetic to politics, otherwise I might have noted Christian conservatives’ previous disinterest in the ballooning national debt during George Bush’s presidency. Amidst two expensive wars on the opposite side of the globe, each of which was waged on some thin connection to 9/11 or another, the national debt doubled in Bush’s eight year term. I don’t remember hearing any panic about the debt from Fox News or Christian news sources back then. Instead, I heard many trite and alogical sayings about “supporting the troops” and “fighting them over there so that we don’t have to fight them here.” Nothing about the dangers of the mounting debt—not even while acknowledging in the same breath the virtue and necessity of the wars.

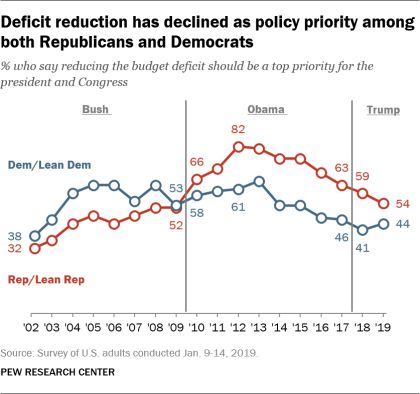

I realize now that even the relatively brief fiscal battle between the likes of President Obama and Paul Ryan was a byproduct of the election cycle. In the wake of the Great Recession and with the tailwind of a Tea Party wave in Congress, Republicans whipped up fear of the Democrats’ spending spree. Deficit reduction as a policy priority peaked among Republicans in the election year of 2012, declining thereafter.

After the GOP loss in 2012, elected Republicans had less and less use for anti-deficit rhetoric, especially as Medicare and Social Security benefits increased as a percentage of federal spending. Seniors, the beneficiaries of these gargantuan entitlement programs, are reliable GOP voters. Hence, Donald Trump’s campaign promise in 2015 not to touch entitlement spending—and his subsequent victory in the GOP primary—should be seen as the continuation of a trend, rather than as a sudden break from trend. It was a reversion to the pre-Obama mean.

When GOP leaders don’t make the national debt a priority or emphasize the danger of it, neither do conservative media figures or evangelical leaders. Even in the midst of a pandemic, anxiety about deficit spending has continued to fall. According to Pew Research, 55% of US adults called the fiscal deficit a “very big problem” in the Fall of 2018, while only 47% did in June, 2020.

This comes as the United States passes several major debt milestones. Publicly held federal debt (not held by government programs) will surpass 100% of GDP this year. Total private and public debt will almost certainly shoot above 400% of GDP, cresting the previous peak reached in 2008. And this year’s fiscal deficit is projected to be $3.7 trillion—about as much as the deficits of the last six years combined.

Naturally, a populist cynicism about the national debt has crept into the political landscape that views anti-deficit arguments merely as underhanded attempts to suppress the spending goals of the other party. It doesn’t help that economists’ arguments about the (eventual) negative effects of a national debt buildup have consistently been wrong.

The CBO and other nonpartisan organizations have warned for years and years that rapid growth in the supply of Treasuries on the market would overwhelm demand from savers and lead to a sharp rise in interest rates, thus sparking a debt crisis. That hasn’t happened for three reasons: first and most importantly, as demonstrated by the Bank of International Settlements and others, national debt buildups beyond a certain percentage of GDP weigh on economic growth, which then lead investors back to the safe yields of Treasuries. Second, the US enjoys the privilege of issuing the world’s primary reserve currency, and plenty of foreign credit market participants issue debt in US dollars—meaning that they continually need more of them over time. Third, partially as a result of the weak economic growth brought on by excessive debt, US population growth has been slowing for decades, which has made the massive Baby Boomer generation (or their pension fund managers) more dependent on a scarce supply of interest-bearing assets to fund their retirement.

Despite the skyrocketing national debt, the worst effects of it won’t be a spike of interest rates or inflation (at least in the short term), but rather an extremely weak recovery from the pandemic and ever-slower economic growth thereafter. Eventually, it will lead policymakers to adopt Modern Monetary Theory as an excuse to print money for fiscal spending, rather than going through the debt markets. That’s when we’ll see inflation begin to spike, and interest rates will follow it higher (because who wants to be paid interest that can’t keep up with rising prices?). And in our heavily indebted economy, the mass defaults and debt restructuring brought on by a spike in interest rates will be incredibly painful.

The chickens, as they say, will finally come home to roost. (I’ve written at length about this process that I call the “Monetary Death Spiral” here, here, and here.)

Republicans could have done something to stop or at least curb this trajectory, but instead they turned a blind eye to it. They elected Donald Trump, who has ushered in a new branch of nationalist conservatism that is unapologetic about spending on such issues as a border wall, massive infrastructure projects, and any number of other pet projects. Meanwhile, the “GOP’s rank deficit hypocrisy is empowering liberals who view concerns about fiscal soundness as barriers to political and policy success,” writes Peter Suderman for the May, 2020 issue of Reason Magazine. “Republicans under Trump [have] … made it even harder to find a politically plausible way of righting the nation’s fiscal trajectory.”

I still think that Christian conservatives meant it when they warned about the “immorality” of the rising national debt. They knew, more so than the average liberal, that you can’t live beyond your means forever. Eventually, your credit runs out and the bill comes due. But more important to them was to protest the speck in Democrats’ eyes. “Behind closed doors”—when it benefited them politically to look the other way—the planks in their own eyes (massive debt expansion under a GOP president) didn’t matter—or else they were genuinely and willfully blinded to them. The debt crisis that will come at some point down the road lost priority to the here and now. Short-term thinking prevailed over discipline, delayed gratification, and self-restraint. Political power took precedence over moral principles.

At some point, like a ship with decaying structural integrity, the lack of integrity among Christian conservatives and other fiscal hawks when it comes to the national debt will have destructive consequences.

Articles posted on LCI represent a broad range of views from authors who identify as both Christian and libertarian. Of course, not everyone will agree with every article, and not every article represents an official position from LCI. Please direct any inquiries regarding the specifics of the article to the author.

Did you read this in a non-English version? We would be grateful for your feedback on our auto-translation software.

), //libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

), https://libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

), https://libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

), https://libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

), https://libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

*by signing up, you also agree to get weekly updates to our newsletter

Sign up and receive updates any day we publish a new article or podcast episode!