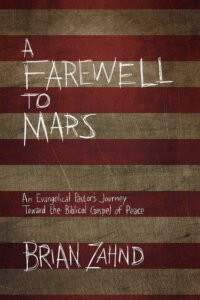

Brian Zahnd is the founder and lead pastor at Word of Life Church in St. Joseph, Missouri. He is the author of several books, most recently A Farewell to Mars (review here), where he recounts his journey to the gospel of peace after many years of marching to the drumbeats of war. His journey will resonate with libertarians who are disenchanted with the state of political affairs in the United States, as well as with many Christians who hunger for a gospel that speaks to human social needs.

Brian Zahnd is the founder and lead pastor at Word of Life Church in St. Joseph, Missouri. He is the author of several books, most recently A Farewell to Mars (review here), where he recounts his journey to the gospel of peace after many years of marching to the drumbeats of war. His journey will resonate with libertarians who are disenchanted with the state of political affairs in the United States, as well as with many Christians who hunger for a gospel that speaks to human social needs.

Zahnd agreed to discuss the themes of his new book with somebody who has a libertarian Christian audience in mind. My questions were shaped in part by my desire to connect the core issues that matter to me as a libertarian – primarily violence and peace – with my belief that the gospel of Jesus will change human society. I do not assume or expect Zahnd to agree with libertarians on politics, but I do believe our views overlap enough to have a unique conversation. I have also tried to avoid questions he has already answered in the book.

Brian,

Thank you for being willing to discuss with me the themes in your new book. As I was reading it, I knew it would resonate with my fellow libertarians. We have a reputation of being contrarians, especially in politics! Many of us are strongly anti-war. The non-aggression principle is foundational to our political beliefs. We strongly affirm Lord Acton’s famous quote on the corruption of absolute power. It is no surprise that anyone who teaches that Jesus spoke against empire ends up on our radar!

DS: On this issue of peace and violence, what criticisms have you experienced? What do you believe your critics are missing most about the message of Jesus? How has their critique affected the way you understand and communicate this message?

BZ: First of all, Doug, thank you for the opportunity to engage with your audience.

We tend to divide the subject of violence into two categories: individual/criminal violence and corporate/civil violence. If I speak of the problem of violence on the level of the individual — street violence, domestic violence, criminal violence — I receive no criticism at all. But if I call into question the organized mass violence of war, I have to brace myself for withering criticism. The violence of war is sacred violence. It’s hallowed in anthem, memorial, monument, and myth. The massive violence of war is sacred because it has been the organizing principle of civilization. This is the story that history (and the Bible) tells us. This is the foundational story of Cain and Abel. Cain re-imagined his brother as a rival and enemy. So Cain killed Abel. Then Cain lied to God and himself about what he had done, moved east of Eden, and founded the first city. This is how the Bible tells the story of the rise of human civilization as we build upon a foundation of collective murder. Over the course of six millennia human civilization has clung to power enforced by violence as our organizing principle, and most people find it nearly impossible to imagine the world any other way.

In speaking on the subject of violence it’s important to keep in mind that I’m exclusively addressing those who identify themselves as followers of Jesus. The views I hold on the possibility of nonviolence are not “self-evident” — to use Jefferson’s Enlightenment term. These views are only intelligible if God validated and vindicated Jesus Christ by raising him from the dead. What I think my Christian critics have missed most of all is that Jesus’ message was not about how to get into heaven when we die, but how to bring the government (kingdom) of God into the world here and now. But rethinking how we arrange the world is such a radical undertaking that it needs to be told somewhat slant so that it can dawn on people slowly. This is why Jesus spoke in parables — not to “illustrate his point,” but to keep his message from being too pointed too quickly. In challenging violence as our organizing principle I’m reminded of what Emily Dickinson said,

Tell all the truth but tell it slant —

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth’s superb surprise

As Lightning to the Children eased

With explanation kind

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind —

DS: In order to avoid claiming Jesus would endorse a particular political party or policy, many Christians make the claim that Jesus wasn’t political. They quote Jesus when he said, “My kingdom is not of this world.” Why is it so difficult to convince Christians that the message of Jesus is as much for our social ordering as it is for our personal lives?

BZ: The irony is that Jesus message was intensely political. But it was not then and is not now an endorsement of any of the existing politics of power. Jesus cannot be enlisted to endorse our own preferred version of politics for the simple reason that he has his own politics. Jesus calls his politics “the kingdom of God/heaven.” When Jesus says, “my kingdom is not of this world,” he is explaining to the Roman governor Pontius Pilate that his kingdom is not from the system of violent of power, the system of Caesar. The kingdom of Christ is for this world, but it is not from the world as we have known it. The kingdom of Christ is without coercion. As Christians we persuade by love, witness, Spirit, reason, rhetoric, and if need be, by martyrdom, but never by force. Yet we are deeply invested in our politics of power — especially if the present arrangement has us situated somewhere near the top. So instead of making the radical decision to live as if Jesus is actually Lord of the nations, we relegate him to Secretary of Afterlife Affairs. It’s a clever move, but it completely obscures the political message of Jesus.

I’m fielding your questions from Lisbon, and last week I gave an interview to a Portuguese television station. I was asked, “Why is the church relevant?” I said, the question isn’t why is the church relevant, but if the church is relevant. Jesus is the one who is eternally relevant. Jesus is the one who has something to say. Jesus is the one who offers the world a hope beyond the dead end of violence based politics. To the extent that the church dares to embody the radical politics of Jesus it is relevant. But to the extent that the church is unfaithful to the Lordship of Jesus, it is irrelevant and deserves the disinterest of the world.

DS: Violence as the “organizing principle of civilization” is an unfamiliar theme to many Christians. It could very easily be misunderstood. You elaborate on this in your book, but where should readers look for more information after they finish yours? What author(s) or book titles have you appreciated most along your journey toward peace?

BZ: I’ve been very influenced by John Howard Yoder and René Girard. Yoder’s landmark book is The Politics of Jesus and I highly recommend it. I suppose the place to start with René Girard is either The Girard Reader or I See Satan Fall Like Lightning. But these books are written for a primarily academic audience. A more accessible book might beResident Aliens by Stanley Hauerwas and Will Willimon.

DS: Most libertarian Christians are highly suspicious of centralized power. We contend that when power becomes increasingly concentrated, it becomes increasingly corrupt and more harmful to society. You strongly oppose the idea of empire in your book, especially when the empire claims to have God on its side. Few Christians (even Christian anarchists) would deny that governance is needed, but at what point does government become empire? Are local governments less likely to become satanic than federal governments?

BZ: I loosely define empires as rich, powerful nations who seek to rule other nations and claim a manifest destiny to direct history. As a Christian I am opposed to empire for the simple reason that what empires claim for themselves, God has given to Christ. God loves nations, but is opposed to empire. So, yes, smaller is better. This is where I think we should all listen to Wendell Berry. If there is a prophet in America today it’s Wendell Berry.

DS: Many readers of this interview are reticent to vote or participate in government because doing so feels like endorsing an evil system. It is, in essence, telling the state, “You have my blessing to use violence.” If Jesus would not today endorse any existing politics of power, what advice do you have for Christians who are given the opportunity to give Caesar their opinion through voting? How should we navigate the complex arrangement of government in our country without selling out to empire?

BZ: This is a question I constantly struggle with. I can make a case for not voting along the lines with the example you give. On the other hand, John Howard Yoder felt that Christians have an obligation to vote for those least likely to employ the means of violent power. I tend toward having very little engagement with the machinations of politics, but I try resist the lure of Christian anarchy. It’s tricky. I do make a distinction between war and police function. I know at times the line becomes quite blurred, but in the end I do think there is a distinction.

DS: Both the Religious Right and the Christian Left seem to want the U.S. federal government to adopt policies that reflect God’s will for human social flourishing. Their efforts are largely to lobby the government for their preferred blend of policy proposals that ostensibly accomplish God’s will. In order to base human social order on the teachings of Jesus, does government play a role? Is it possible for empire to have God on its side if it achieves outcomes that are aligned with the teachings of Jesus?

BZ: Obsession with outcomes makes following Jesus nearly impossible. When Jesus called his disciples to follow him, he called them to take up their cross. The implication was that to follow Jesus one must be willing to die. As Dietrich Bonhoeffer famously said, “When Christ calls a man he bids him come and die.” The cross is the antithesis of the sword. The politics of power always has the sword of violence at the center — no matter how well concealed. The alternative society of Christ has a cross at the center. On Good Friday Jesus re-founded the world. Instead of being organized around an axis of power enforced by violence, the world is now to be organized around an axis of love expressed in forgiveness. This is, of course, very radical. And I make no apology for it. The church is the world as believing in Christ and nothing less.

DS: In the book you share a profound experience you and your wife had where you witnessed a blatantly idolatrous image of Christianity coupled with American militarism. Using brazen examples to demonstrate this kind of idolatry may have the opposite effect on readers whose beliefs are more tempered. They might simply respond, “My church doesn’t worship America, we worship Jesus and love America. We have a balanced view.” Indeed, many churches proudly display the American flag in their sanctuaries, or pay tribute to church members who are soldiers on bulletin boards in their hallways (often with “supporting” Bible verses about strength or might!). At what point does one’s respect and admiration for the United States as a nation become idolatrous? Is there a “balanced view”? How far is too far?

BZ: I love America too. It’s my home. Praying for church members who are soldiers will be an inevitable expression of love. One of my closest friends is a Lieutenant Colonel in the U.S. Army. He’s been stationed in Afghanistan for the past year. I’ve prayed for him every day — I’ve prayed that he would return home safely to his family and future. (He returned home just last week.) The problem I have with “praying for our troops” is the possessive pronoun “our.” I saw a church that had banner on the side of its building that said, “We pray for our troops.” But what do they mean by “our”? Does the church have troops? No. Then in what sense are they “our” troops? In the two World Wars the churches in every warring nation were praying for “our” troops. Do you see the madness of it? As far as flags in sanctuaries go, I think they are entirely out of place there. I was just in Portugal and the churches had national flags in their sanctuaries, with I regarded as mostly benign. But when I see American flags in churches in America and Russian flags in churches in Russia, I’m afraid that in the end these flags of empire will obscure the cross. Worse yet, is when I see a church with the American flag and the Christian flag on the same flag pole. Of course, you know which one is on top. And if one argues that it’s no big deal, just reverse them and see how big a deal it is! I think that says it all.

DS: Your books and sermons often return to the cross. Why must Christians return to the cross to find our way in the world? Can we not rely on other parts of the Bible to know how God wants humans to manage society? For instance, God directly gave Israel many laws to order their society. Is that God’s opinion on “good government”? How do we let the cross become the transformational experience that upends the violence of the world systems?

BZ: The cross, not the Bible, is the center of the Christian faith. If we rely on the Bible alone we are not even able to make a clear denunciation of slavery! This was a real problem for American evangelicals in both the North and the South in the decades leading to the American Civil War. Mark Noll brings this out in his important little book, The Civil War As A Theological Crisis. What I often see people do is use the Old Testament to trump the Sermon on the Mount. “Sure, Jesus talked about turning the other cheek, but don’t forget that God commanded Joshua to kill all those Canaanites.” They use Joshua to countermand Jesus! The Old Testament is the inspired telling of Israel’s story as they come to know the living God, but it all leads to Jesus. And Jesus’ life leads to the cross. The cross is where human systems of violent religion and politics are dragged into the light and shown to be so evil that they are capable of the greatest sin of all: The murder of God. Judaism was the pinnacle religion and Rome was the noblest of politics…but they killed Jesus! In the light of the cross we are to repent of violence as a legitimate means of shaping the world and opt instead for the Jesus way.

DS: Jesus wept over Jerusalem, wishing they knew “the things that made for peace.” What do you weep over for your congregation? Your city? Your country?

BZ: I weep that so much of the American church is unwittingly entangled with an idolatrous allegiance to nationalism, militarism, violence, guns, and war. I weep that the Constantinian strategy of separating Jesus from his ideas is still so effective. I weep that so many who profess to follow Jesus cynically dismiss the way of peace as naive and impossible. Yes, I weep over these things. But I also have hope.

DS: Do you have any other writing projects on the horizon? Can we get a peek?

BZ: I’m about halfway through a new book with the working title of Water To Wine. It’s largely my story of moving beyond a paper-thin evangelicalism and into the richness of the Great Tradition of the Christian faith.

), //libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

), https://libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

;?>/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/sqb-registration-img.jpg)