Originally by Edmund Opitz in the July 1991 (41) edition of The Freeman.

—-

The First Amendment to the Constitution forbids Congress to set up an official church; there was to be no “Church of the United States” as a branch of this country’s government. Such an alliance between Church and State is what “establishment” means. An established church is a politico-ecclesiastical structure that receives support from tax monies, advances its program by political means, and penalizes dissent. Our Constitution renounces such arrangements in toro; the Founders wrote the First Amendment into the Constitution to prevent them.

The famed American jurist Joseph Story, who served on the Supreme Court from 1811 till 1845, and is noted for his great Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, had this to say about the First Amendment: “The real object of the Amendment was, not to countenance, much less advance Mahometanism, or Judaism, or infidelity, by prostrating Christianity; but to exclude all rivalry among Christian sects, and to prevent any national ecclesiastical establishment, which should give to an hierarchy the exclusive patronage of the national government.”

The various theologies, doctrines, and creeds found in this country can thus be advanced by religious means only—by reason, persuasion, and example. Separation of Church and State means that government maintains a neutral stance toward our three biblically based religions—Catholicism, Judaism, and Protestantism, as well as toward the various denominations and splinter groups. These several religious bodies, then, have no alternative but to compete for converts in the marketplace of ideas. This is a good arrangement, good for both Church and State; it avoids the twin evils of a politicized religion and a divinized politics.

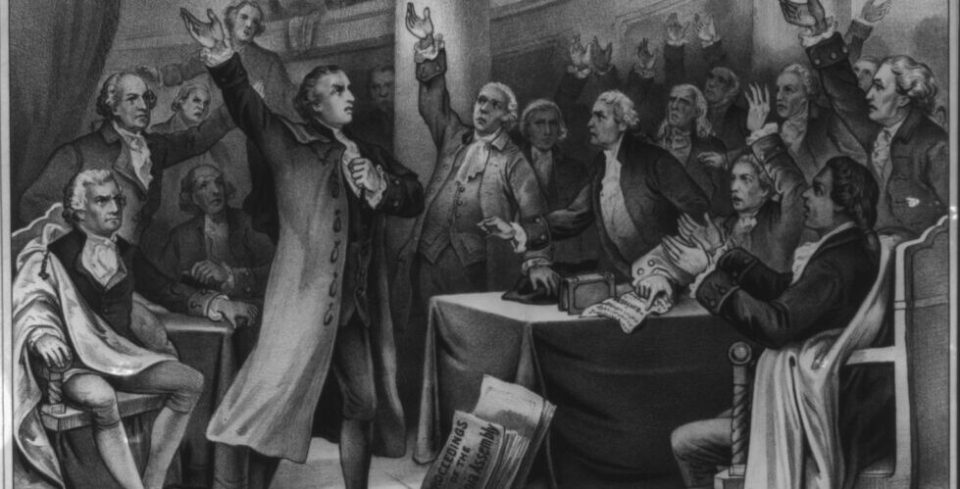

A Christian Nation

It has often been observed that America is a Christian nation — around which observation several misunderstandings cluster. We are a Christian nation in the sense that our understanding of human nature and destiny, the purpose of individual life, our convictions about right and wrong, our norms, emerged out of the religion of Christendom — not out of Buddhism, Confucianism, or primitive animism. And it is a fact of history that our forebears whose religious convictions brought them to these shores in the 17th and 18th centuries sought to create in this new world a biblically based Christian commonwealth. But it was not to be a theocracy — of which the world had seen too many! It was to be a religious society, but one which incorporated a secular political order!

The reasoning ran something like this. The human person is forever; each man and woman lives in the here and now, and also in the hereafter. Here, we are pilgrims for three score years and ten, more or less. Life here is vitally important for it’s a test run for life hereafter. Earth is the training ground for life eternal. Such training is the essence of religion, and it’s much too important to be entrusted to any secular agency. But there is a role for government; government should maintain the peace of society and protect equal rights to life, liberty, and property. This maximizes liberty, and in a free social order men and women have maximum opportunity to order their souls aright.

Separating the sacred and the secular in this fashion is a new idea in world history. Secularize government and you deprive it of the perennial temptation of governments to offer salvation by political contrivances. By the same token, things sacred are privatized as free churches, where the spiritual concerns of men and women are advanced by spiritual means only.

So, when it is said that America is a Christian nation, the implication intended is poles apart from what is meant when it is observed, for example, that Iran is a Shiite nation. The Shiite sect of Islam is a branch of the government of Iran. Other religions are not tolerated. Deviations from doctrinal orthodoxy are forbidden. The government punishes infidels because Shiism is Iran’s official, authorized church. From time to time government uses the sword to gain converts. The government of Iran is not neutral with respect to religion.

In the United States, it is mandated that the government maintain a level playing field, so to speak, “a free field and no favor,” where freely choosing individuals find their different pathways to God while government merely keeps the peace. This is what is really meant by the phrase, “Separation of Church and State.” This oft-quoted phrase is frequently misunderstood as suggesting that religion and politics are incompatible, and that we should keep religion out of politics.

If we think of “politics” as several candidates wheeling, dealing, and slugging it out in an election campaign, it’s clear that religion doesn’t have a significant role in such a situation. And if we think of “religion” in terms of a contemplative meditating and praying in his cell, it’s obvious that politics is absent. But there is no coherent political philosophy apart from a foundation of religious axioms and premises.

Religion and the Social Order

Religion, at its fundamental level, offers a set of postulates about the universe and man’s place therein, including a theory of human nature, its origin, its potentials, and its destination. Religion deals with the meaning and purpose of life, with man’s chief good, and the meaning of right and wrong. Thus, religious axioms and premises provide the basic materials political philosophy works with. The political theorist must assume that men and women are thus and so, before he can figure out what sort of social and legal arrangements provide the fittest habitat for such creatures as we humans are. So, some religion lies at the base of every social order.

It is the religion of dialectical materialism that is the take-off point for the Marxian theory and practice of the total state. Hinduism is basic to the structures of Indian society. Western society, Christendom, was shaped and molded by Christianity. Incorporated into Western civilization were elements from the Bible, as well as ingredients from Greece and Rome. This composite was lived, worked over, and thought out for nearly 1800 years by the peoples of Europe. And then something new emerged and began to take root in the New World; it was the recovery of that part of the Christian story needed to ransom society from despotism and erect the structures of a free society wherein men and women might enjoy their birthright of economic and political liberty.

A vision emerged of a society where men and women would be free to pursue their personal goals, unimpeded by the fetters of rank, privilege, caste, or estate that had hitherto consigned people to roles determined by custom and command, not by their own choice.

The people who settled these shores during the 17th and 18th centuries were children of the Reformation driven by their need to worship God as it pleased them, according to their own wisdom and conscience. Believing that God had entered into a covenant with His people, they freely covenanted together to form churches. This was later called “the gathered church idea,” seemingly endorsed by Jesus himself in Matthew 18:20: “Where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them.”

The local New England church in the Puritan period had full ecclesiastical authority to ordain its minister and appoint deacons and elders. Its minister could celebrate communion, perform christenings, baptisms, and marriages, and conduct funerals — all on the authority of the local church. Each church was in voluntary fellowship with other churches, but in authority over none. The covenant pattern of the early New England churches was the paradigm for the federalist political structure erected two centuries ago. The West was moving from status to contract, as Sir Henry Maine would observe in 1861.

This concern for individual liberty in society was not limited to theologians. Tom Paine generally took a critical stance when dealing with religion and the church, but in 1775 in an essay entitled “Thoughts on Defensive War” he wrote as follows: “In the barbarous ages of the world, men in general had no liberty. The strong governed the weak at will; ‘till the coming of Christ there was no such thing as political freedom in any part of the world… The Romans held the world in slavery and were themselves slaves of their emperors… Wherefore political as well as spiritual freedom is the gift of God through Christ.” And Edward Gibbon, so critical of the Church in his history of Rome, nevertheless pays tribute to “… those benevolent principles of Christianity, which inculcate the natural freedom of mankind.”

Our forebears of a couple of centuries ago regarded human freedom as a religious imperative. They loved to quote such biblical texts as: “Where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is liberty,” (2 Cor. 3:17) and “Proclaim liberty throughout all the land to all the inhabitants thereof.” (Lev. 25:10) They struggled for freedom of worship; they fought for the right to speak their minds, and for a free press to put their convictions into written form. They also had firm convictions about private property. The popular slogan of the time was “Life, Liberty, and Property!” Property meant the right of private ownership. Adam Smith and his Wealth of Nations came along at just the right time—with what Smith called his “liberal plan of liberty, equality and justice”—to become the economic counterpart of the political ideas of the Declaration of Independence.

The Importance of the Individual

The central doctrine of the American political system is our belief in the inviolability of the individual man or woman. This is one of the self-evident truths enunciated in the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.” The “equality” which is the key idea of the Declaration means “equal justice,” the Rule of Law, the same rules for everybody because we are one in our essential humanity.

The reflections of H.L. Mencken on this point are intriguing as coming from a man usually critical of religion. In 1926 Mencken wrote an essay entitled “Equality Before the Law.” “Of all the ideas associated with the general concept of democratic government,” he wrote, “the oldest and perhaps the soundest is that of equality before the law. Its relation to the scheme of Christian ethics is too obvious to need statement. It goes back, through the political and theological theorizing of the middle ages, to the early Christian notion of equality before God… The debt of democracy to Christianity has always been underestimated… Long before Rousseau was ever heard of, or Locke or Hobbes, the fundamental principles of democracy were plainly stated in the New Testament, and elaborately expounder by the early fathers, including St. Augustine.

“Today, in all Christian countries, equality before the law is almost as axiomatic as equality before God. A statute providing one punishment for A and another for B, both being guilty of the same act, would be held unconstitutional everywhere, and not only unconstitutional, but also in plain contempt of common decency and the inalienable rights of man. The chief aim of most of our elaborate legal machinery is to give effect to that idea. It seeks to diminish and conceal the inequities that divide men in the general struggle for existence, and to bring them before the bar of justice as exact equals.”

The freedom quest of Western man, as it has exhibited itself periodically over the past 20 centuries, is not a characteristic of man as such. It is a cultural trait, philosophically and religiously inspired. The basic religious vision of the West regards the planet earth as the creation of a good God who gives a man a soul and makes him responsible for its proper ordering; puts him on earth as a sort of junior partner with dominion over the earth; admonishes him to be fruitful and multiply; commands him to work; makes him a steward of the earth’s scarce resources; holds him accountable for their economic use; and makes theft wrong because property is right. When this outlook comes to prevail, the groundwork is laid for a free and prosperous commonwealth such as we aspired to on this continent.

A Created Being in a Created World

We gaze out upon the world around us and are struck by the preponderance of order, harmony, beauty, balance, intelligence, and economy in the way it works. The thought strikes us that the explanation of the world is not contained within the world itself, but is to be sought in a Source outside the world. The Bible simply declares that God created the world, and when He had finished He looked out upon the world He had created and called it good. The biblical world is not Maya — as Hinduism calls its world; it is not a mirage or an illusion. Nor is the world of nature holy; only God is holy. The created world, including the realm of nature, is “the school of hard knocks.” The earth challenges us to understand its workings so that we might learn to use it responsibly to serve our purposes. Economics and the free enterprise system teach us how to use the planet’s scarce resources providently, efficiently, and non-wastefully—in order to produce more of the things we need.

Man comes onto the world scene as a created being. As a created being, man is a work of divine art and not a mere happening; he possesses free will and the ability to order his own actions. As such, he is a responsible being. He’s no mere chance excrescence tossed up haphazardly by physical and chemical forces, shaped by accidental variations in his environment. To the contrary, man is endowed with a portion of the divine creativity, giving him the power to dynamically transform himself, and his environment as well, according to his needs and his vision of what ought to be.

The other orders of creation — animals, birds, bees, fish, and so on — live by the dictates of their instincts. But our species has no such infallible inner guidelines as our fellow creatures possess; our guidelines are formulated in the moral code, as summed up in the Ten Commandments.

Ethical relativism is a popular attitude today; it is a wrong answer to questions such as: Is there a moral code? Are there moral laws? Let me summarize briefly the argument that our universe has a built-in moral order by showing that there is a striking parallel between the laws of physical nature and moral laws.

The laws of science transcribe into words the observed causal regularities in the world of physical nature, i.e. the realm of things which can be measured, weighed, and counted. This is one sector of reality. Reality also exhibits a moral dimension, where things are valued or disdained on a scale of ethics ranging from good to evil. Biological survival depends on conforming our actions to the laws of nature; ignorance is no excuse. Social survival, the enhancement of individual life in society, depends on willing obedience to the moral code that condemns murder, theft, false witness, and the rest. Transgressors lead us toward social decay and cultural disorder.

Your individual physical survival depends on several factors. If you want to go on living you need so many cubic feet of air per hour, or you suffocate. You need a minimum number of calories per day, or you starve. If you lack certain vitamins and minerals specific diseases will appear. There is a temperature range within which human life is possible: too low and you freeze, too high and you roast. These are some of the requirements you must meet for individual bodily survival. They are not statutory requirements, nor are they mere custom. They are laws of this physical universe, which one can deny only at his peril.

Establishing a Moral Order

It is just as obvious that our survival as a community of men, women, and children depends on meeting certain moral requirements: a set of rules built into the nature of things which must be obeyed if we are to survive as a society — especially as a social order characterized by personal freedom, private property, and social cooperation under the division of labor.

Moses did not invent the Ten Commandments. Moses intuited certain features of this created world that tell us what we must do to survive as a human community, and he wrote out the code: Don’t murder, don’t steal, don’t assault, don’t bear false witness, don’t covet. Similar codes may be found in every high culture.

It would be impossible to have any kind of a society where most people are constantly on the prowl for opportunities to murder, assault, lie, and steal. A good society is possible only if most people most of the time do not engage in criminal actions. A good society is one where most people most of the time tell the truth, keep their word, fulfill their contracts, don’t covet their neighbor’s goods, and occasionally lend a helping hand. No society will ever eliminate crime, but any society where more than a tiny fraction of the people exercises criminal tendencies is on the skids. To affirm a moral order is to say, in effect, that this universe has a deep prejudice against murder, a strong bias in favor of private property, and hates a lie.

The history of humankind in Western civilization was shaped and tempered by biblical ideas and values, and the attitudes inspired by these teachings. There was much backsliding, of course; but in the fullness of time scriptural ideas about freedom, private property, and the work ethic found expression in Western custom, law, government, and the economy — especially in our own nation. We prospered to the degree that we practiced the freedom we professed; we became ever more productive of goods and services. The general level of economic well-being rose to the point where many became rich enough so that biblical statements about the wealthy began to haunt the collective conscience.

The Bible does warn against the false gods of wealth and power, but it legitimizes the normal human desire for a modicum of economic well-being — which is not at all the same as idolizing wealth and/or power. As a matter of fact, the Bible gives anyone who seeks it out a general recipe for a free and prosperous commonwealth. It tells us that we are created with the capacity to choose; we are put on an earth which is the Lord’s and given stewardship responsibilities over its resources. We are ordered to work, charged with rendering equal justice to all, and to love mercy. A people which puts these ideas into practice is bound to become better off than a people which ignores them. These commands laid the foundation for the economic well-being of Western society.

Western civilization, which used to be called “Christendom,” did not prosper at the expense of the relatively poor Third World. This unhappy sector of the globe is poor because it is unproductive; and it is unproductive because its nations lack the institutions of freedom that enabled us to achieve prosperity.

During recent years a small library of books and study guides has poured off the presses of American church organizations (and from secular publishers as well) with titles something like “Rich Christians (or Americans) in a Hungry World.” The allegation is that our prosperity is the cause of their poverty; in other words, the Third World has been made poor by the very same economic procedures — “capitalism” — that have made Western nations prosperous! Therefore — the argument runs — our earnings should be taxed away from us and our goods should be handed over to Third World countries—as a matter of social justice! The false premise is that the wealth we have labored to produce has been gained at their expense. Sending them our goods, then, is but to restore to the Third World what rightfully belongs to it! What perverse ignorance of the way the world works!

Nations of the West were founded on biblical principles of justice, freedom, and a work ethic, which led naturally to a rise in the general level of prosperity. Our wealth could not have come from the impoverished Third World where there was a scarcity of goods. We prospered because of our productivity; we became productive because we were freer than any other nation, Freedom in a society enables people to produce more, consume more, enjoy more; and also to give away more—as we have done—to the needy in this land and in lands all over the world. The world has never before witnessed international philanthropy on such a scale.

No one has denied Third World nations access to the philosophical and religious credo which has inspired the American practices that make for economic and Social wen-being. Few nations have done more to make the literature of liberty available to all who wish it than American missionaries, educators, philanthropists, and technicians. But there is something in the creeds of Third World countries that hinders acceptance. However, when non-Christian parts of the world decide to emulate Western ideas of economic freedom they prosper. Look what happened to the economies of Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Singapore when they turned the market economy loose!

Regarding the Poor

Ecclesiastical pronouncements on the economy are fond of the phrase “a preferential option for the poor.” It is invoked as the rationale for governmental redistribution of wealth, that is, for a program of taxing earnings away from those who produce in order to subsidize selected groups and individuals. But it is a fact that reshuffling wealth by programs of tax and subsidy merely enriches some at the expense of others; the nation as a whole becomes poorer. Private enterprise capitalism is, in fact, the answer for anyone who really does have a preferential option for the poor. The free market economy, wherever it has been allowed to function, has elevated more poor people further out of poverty faster than any other system.

Another phrase, repeated like a mantra, is “the poor and oppressed.” There is, of course, a connection between these two words; a person who is oppressed is poorer than he would be otherwise. Oppression is always political; oppression is the result of unjust laws. Correct the injustice by repealing unjust laws; establish political liberty and economic freedom. But even in the resulting free society, where people are not oppressed, there will still be some people who are relatively poor because of the limited demand for their services. Teachers and preachers are poor compared to rock musicians because the masses spend millions to have their ears assaulted by amplified sound, in preference to the good advice often available for free!

Ecclesiastical documents announce their concern for “the poor and oppressed,” but the authors of these documents are completely blind to the forms oppression may take in our day. If there are unjust political interventions that deny people employment, this would seem to be a flagrant case of oppression. There are many such interventions. Minimum wage laws, for instance, deny certain people access to employment, and these people are poorer than they would be otherwise; the entire nation is less well off because some people are not permitted to take a job. The same might be said of the laws that grant monopoly status to certain groups of people gathered as “unions” – U.A.W., Teamsters, and the like. The above-market wage rate they gain for union members results in unemployment for others both union and nonunion. It is not difficult to figure out why this is so. The general principle is that when things begin to cost more we tend to use less of them. So, when labor begins to cost more, fewer workers will be hired.

It would take several pages to list all of the alphabet agencies that regulate, control, and hinder productivity, making the entire nation less prosperous than it need be. Our country suffers under these oppressions, economically and otherwise, but not so severely as the oppressed people of other nations, especially Communist and Third World nations. Churchmen recommend, as a cure for Third World poverty, that we deprive the already over-taxed and hampered productive segment of our people of an even larger portion of their earnings, so as to turn more of our money over to Third World governments. This will further empower the very Third World politicians who are even now oppressing their people, enabling those autocrats to oppress them more efficiently!

The New Testament and the Rich

It is not difficult to rebut the manifestoes issued by various religious organizations. But then we turn to certain New Testament writings and are confronted by what seem to be condemnations of the rich. How, for example, shall we understand Jesus’ remark, found in Luke 18:25 and Matthew 19:24: “It is easier for a camel to go through a needle’s eye, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God”?

Jesus’ listeners were astonished when they heard these words. Worldly prosperity, many of them assumed, was a mark of God’s favor. It seemed to follow that the man whom God favored with riches in this life was thereby guaranteed a spot in heaven in the next.

There is a grain of truth in this distorted popular mentality. Biblical religion holds that man is a created being, with the signature of his Creator written on each person’s soul. This inner sacredness implies the ideal of liberty and justice in the relations between person and person. These free people are given dominion over the earth in order to subdue it, working “for the glory of the Creator and the relief of man’s estate,” as Francis Bacon put it. This is but another way of saying that those who follow the natural order of things—God’s order—in ethics and economics will do better for themselves than those who violate this order. The faithful, we read in Job 36:11, “… if they obey and serve Him… shall spend their days in prosperity and their years in pleasures.”

Perhaps Jesus had something else in mind as well. Palestine had been conquered by Rome. Roman overlords, wielding power and enriching themselves at the expense of the local population, would certainly supply many examples of “a rich man.” Furthermore, there were those among the subject people who hired themselves out as publicans to serve the Romans by extorting taxes from their fellow Jews. “Publicans and sinners” is virtually one word in the Gospels!

In nearly every nation known to history, rulers have used their political power to seize the wealth produced by others for the gratification of themselves and their friends. Kings and courtiers in the days of slavery and serfdom consumed much of the wealth produced by farmers, artisans, and craftsmen. Today, politicians in Communist, socialist, and welfarist nations, democratically elected by “the people,” share their power with a congeries of special interests, factions, and pressure groups who systematically prey on the economy, depriving people who do the world’s work of over 40 percent of everything they earn.

Many a “rich man” lives on legal plunder, today as well as in times past. Frederic Bastiat’s little book, The Law, familiarizes us with the procedure. The law is an instrument of justice, intended to secure each individual in his right to his life, his liberty, and his rightful property. Ownership is rightfully claimed as the fruit of honest toil and/or as the result of voluntary exchanges of goods and services. But the law, as Bastiat points out, is perverted from an instrument of justice into a device of plunder when it takes goods from lawful owners by legislative fiat and transfers them to groups of the politically powerful. “Robbery is the first labor saving device,” wrote Lewis Mumford, and political plunder is a species of theft. The fact that it is legally sanctioned does not make it morally right; it is a violation of the commandment against theft.

The Israelites had fond memories of King Solomon. “All through his reign,” we read in 1 Kings 4:25, “Judah and Israel continued at peace, every man under his own vine and fig tree, from Dan to Beersheba.” A nice tribute to individual ownership and economic well-being! The Bible has high praise for honestly earned wealth, and it is exceedingly unlikely that Jesus, in the passage we have been considering, intended anything like a general condemnation of wealth, as such.

At this point someone might raise a legitimate question: “Did not Jesus say, in the Sermon on the Mount, ‘Blessed are the poor’?” Well, yes and no. The Sermon on the Mount appears in two of the four Gospels, in Matthew and in Luke. In Luke 6:20 the Beatitude reads: “Blessed are the poor”; but in Matthew 5:3 it is: “Blessed are the poor in spirit.” There’s a discrepancy here; how shall we interpret it?

The Beatitudes were spoken somewhere between 25 and 30 A.D. The Gospels of Matthew and Luke appeared some 50 or 60 years later. Both authors had access to the Gospel of Mark, to fragments of other writings now lost, and to an oral tradition extending over the generations. We do not have the original manuscripts of the Gospels; what we have are copies of copies, and eventually translations of copies into various languages.

Scholars tell us that the Aramaic original of those two words, “the poor,” is am ha-aretz — “people of the land.” The am ha-aretz — at this stage in Israel’s history — were outside the tribal system of Jewish society; they did not have the time or inclination to observe the niceties of priestly law, let alone its scribal elaborations. The work of the am ha-aretz brought them into contact with Gentiles and Gentile ways of life, which in the eyes of the orthodox was defiling. Their status is like that of the people on the bottom rung of the Hindu caste system — the Sudras. Jesus is reminding His hearers that these outcasts are equal in God’s sight to anyone else in Israel, and because of their lowly station in the eyes of society, they may be more open to man’s need of God than the proud people in the ranks above them. The New English Bible provides an interesting slant on this text; it translates “poor in spirit” as “those who know their need of God.”

In short, Jesus is saying that all are equally precious in God’s sight, including the lowly am ha-aretz; He is not praising indigence, as such.

Biblical Interpretation

The Bible is full of metaphor and symbolism and allegory. Literal interpretation usually falls short; proper interpretation demands a bit of finesse… as in the case of St. Paul’s remark about money.

St. Paul declared that “The love of money is the root of all [kinds of] evil.” (1 Tim. 6:10) The word “money” in this context—scholars tell us—does not mean coins, or bonds, or a bank account. Paul uses the word “money” to symbolize the secular world’s pursuit of wealth and power. We tend to become infatuated with “the world.” It’s the infatuation which is evil, for God’s kingdom is not wholly of this world. We are the kind of creatures whose ultimate destiny is achieved only in another order of reality: “Here we have no continuing city.” (Heb. 13:14) Accept this world with all its joys and delights; live it to the full; but remember—we are pilgrims, not settlers. In today’s vernacular, Paul might be telling us: “Have a love affair with this world, but don’t marry it!”

We know that there are numerous unlawful ways to get rich, and these deserve condemnation. But prosperity also comes to a man or woman as the fairly earned reward of honest effort and service. The Bible has nothing but praise for wealth thus gained. “Seest thou a man diligent in his business?” said the author of Proverbs (Pr. 22:29). “He shall stand before kings.” Economic well-being is everyone’s birthright, provided it is the result of honest effort. But we are warned against a false philosophy of material possessions.

This, I think, is the point of Jesus’ parable of the rich man whose crops were so good that he had to build bigger barns. (Luke 12:17) This good fortune was the man’s excuse for saying, “Soul, thou hast much goods laid up for many years; take thine ease, eat, drink, be merry.”

There is a twofold point to this parable. The first is that nothing in life justifies us in resigning from life; we must never stop growing. It has been well said that we don’t grow old, we become old by not growing. The second point is that a material windfall—like falling heir to a million dollars—may tempt a man into the error of quitting the struggle for the real goals in life. Jesus condemned the man who put his trust in riches, who “layeth up treasure for himself and is not rich toward God.” He did not condemn material possessions as such; He taught stewardship, which is the responsible ownership and use of rightfully acquired material goods.

Life here is probative; our three score years and ten are a sort of test run. As St. Augustine put it, “We are here schooled for life eternal.” And one of the important examination questions concerns our economic use of the planet’s scarce resources and the proper management of our material possessions. These are the twin facets of Christian stewardship, and poor performance here will result in dire consequences. Jesus put it very strongly: “If, therefore, you have not been faithful in the use of worldly wealth, who will entrust to you the true riches?” (Luke 16:12)

What does it mean to be “faithful in the use of worldly wealth?” What else can it mean except the intelligent and responsible use of the planet’s scarce resources to transform them by human effort and ingenuity into the consumable goods we humans require not only for survival, but also as a means for the finer things in life? In practice, this means free market capitalism — the free enterprise system — in the production, exchange, and utilization of our material wealth in the service of our chosen goals.

), //libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

), https://libertarianchristians.com/wp-content/plugins/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/template6-latest.jpeg))

;?>/smartquizbuilder/includes/images/sqb-registration-img.jpg)