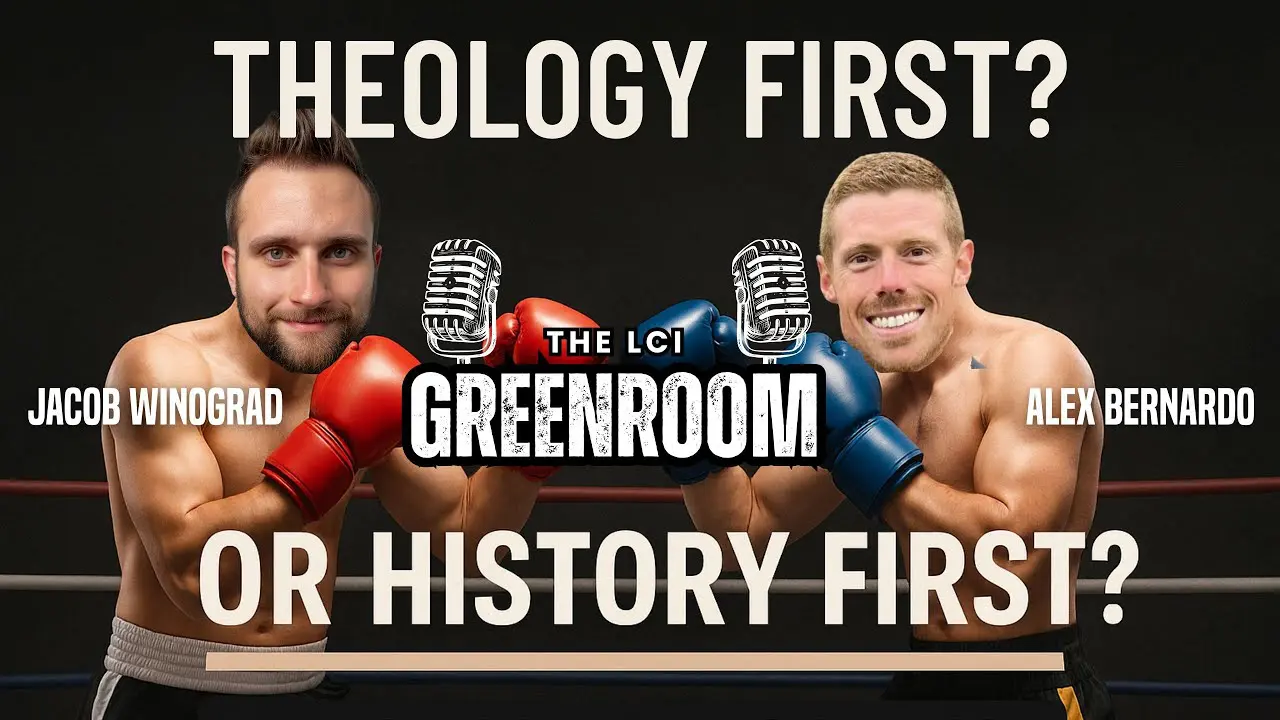

In this episode of the LCI Green Room, host Jacob Winograd converses with Alex Bernardo of the Protestant Libertarian Podcast on the nuanced approaches to reading and interpreting the Bible. They examine the balance between historical-critical methods and systematic theology, discussing how Christians can navigate scripture across various traditions. Specific examples like Romans 13 and the parable of the workers in the vineyard highlight the ongoing debate over these perspectives, stressing the need for humility and open-mindedness in theological interpretation. The episode underscores the significance of considering both historical context and theological principles to fully understand scriptural teachings.

Theology First or History First__ Making Sense of Scripture in Modern Times with Alex Bernardo (1)

===

[00:00:00] Jacob Winograd: When you open your Bible, are you reading history or theology? Is it a collection of ancient documents to be critically examined, or is it the inspired word of God to be read through a theological lens, or is it both? Tonight we’re here to take on one of the most fundamental questions for Christians throughout the ages, but especially today.

[00:00:21] Jacob Winograd: How should we read our Bibles live here tonight that we’re gonna be talking about in the green room?

[00:00:37] Jacob Winograd: Well, good evening everybody, and welcome back to the LCI Green Room. This is the live show of the Libertarian Christian Institute, one of our many shows for the part of the Christians for Liberty network, of which I am the host of the Biblical Anarchy Podcast. And I always like to hold up my little biblical anarchy whiskey glass because that’s just my little bit of merch that I really like to plug, but you can get this in any one of the e either with the main logo or other podcasts here at LCI to have their logos put on there.

[00:01:06] Jacob Winograd: And there’s other good stuff to check out there as well as articles and books. I’m of course holding a copy right here of Faith Seeking Freedom. I haven’t plugged this in a while, so, and we’re currently working on a second edition, so keep your eyes open for that. If you want to actually.

[00:01:22] Jacob Winograd: Know about our projects before they happen. Even get early sneak peeks at them and get to talk to us behind the scenes. You can go to libertarian christians.com/donate, which is the link that’s gonna pop up here at the bottom screen, the ticker right there. Go to that link right there and you can sign up.

[00:01:40] Jacob Winograd: For $10 or more a month to become an LCI insider. And that gets you kind of be behind the scenes access and you have to join a special discord group for those who support what we do here at LCI. And yeah, we just really appreciate it. Things like this podcast, the live shows, the articles, the books wouldn’t be possible without people like you who are listening contributing your hard-earned dollars.

[00:02:02] Jacob Winograd: You know what little, hopefully you have some left after you’ve been taxed to death in this economy and tariffs and all that, adding to the, the never ending damage along with the inflation of the money printer apparatus. But we’re not here tonight to talk about economics and politics per se, because before we even can talk about politics and economics, we have to start with theology, right?

[00:02:24] Jacob Winograd: Theology and the scripture should be sort of what leads us as Christians in terms of how we view the world and how we act in the world. And. Tonight I have a guest who it’s been a little while since he’s been on the Green Room, but he is one of my fellow Christians for Liberty Network podcast hosts here at the Libertarian Christian Institute, and he is the one and only Alex Bernardo of the Protestant Libert Libertarian Podcast.

[00:02:46] Jacob Winograd: Alex, how are you doing tonight? Thanks for being with us.

[00:02:49] Alex Bernardo: I’m

[00:02:49] Jacob Winograd: doing great,

[00:02:49] Alex Bernardo: Jacob, and I’m glad to see that you have your biblical anarchy whiskey glass. I brought my Protestant liver, so cheers for the conversation tonight. Yes, good to be here, man.

[00:02:57] Jacob Winograd: I’m actually in honor of this conversation because you’re a Kentucky man.

[00:03:00] Jacob Winograd: I am drinking, I don’t know if you’ve ever had it, but I had a for Christmas, my brother got me a bottle of puncher chants. I’ve never had that one, which is a Kentucky brewed whiskey. So, it’s rather good. I mean, I’m more of a Jack Daniels guy, and so Jack Daniels is still my, my, my go-to actually Tennessee whiskey.

[00:03:18] Jacob Winograd: But it’s all good. There are a lot of good stuff from Kentucky. I have FA family in Kentucky, and you’re in Kentucky one of these days. Every time I’ve gone through the area, I haven’t had time to meet up with you, but we’ll have to make it happen next time. For sure.

[00:03:29] Jacob Winograd: Alex, go ahead and reintroduce yourself a little bit just for those of who are tuning in who maybe aren’t as familiar with you. You talk about your background and biblical studies and whatnot, and then a little bit of. Plug for the Protestant Libertarian podcast as well.

[00:03:42] Alex Bernardo: Yeah, perfect man.

[00:03:43] Alex Bernardo: Again, thanks for having me back on the night. It’s been a long time, but it’s good to be here and I’m actually excited to have a conversation. It’s not about politics because that does get kind of stale and boring after a while, so this should be a lot of fun. Basically I became a Christian when I was 15 years old and, I was I was raised in the Lutheran church and so I realized that, following Martin Luther, I needed to read my Bible.

[00:04:00] Alex Bernardo: And so I just did that over and over again. Throughout my time in high school and I became so obsessed with it that I went and got a degree in biblical studies and did ministry student ministries for about eight years, bi vocationally after that. Still very much loved the Bible. In 2022, it had been a few years since I had stepped down from ministry and I had started reading political philosophy and I realized that a lot of what I was seeing in the political philosophy happened to correspond with ideas that had arisen in my study of the Bible.

[00:04:25] Alex Bernardo: And so I wanted a space to kind of combine those two things. And so I created the Protestant Libertarian podcast, and that really is what my podcast is. It’s kinda like about the intersection between biblical studies and libertarian political and economic philosophy. As of late I’ve been focusing, I guess more on kind the biblical studies side of things, but a lot of them are methodological issues that have helped me.

[00:04:44] Alex Bernardo: Come to the kinds of conclusions that allowed me to see how compatible libertarianism is with Christianity. And so I explore all that stuff on my show. I talk to a lot of cool biblical scholars. I have some really great interviews coming up. I’m actually interviewing Bob Murphy next week, which I’m stoked about having him on the show to talk about the Federal Reserve.

[00:04:59] Alex Bernardo: And there’s been a lot of good books published by some incredible scholars in the last couple of months. And so I got some good ones lined up. So the fall schedule is looking real good for the show.

[00:05:10] Jacob Winograd: Yeah, right on. I’ve had Bob on the show a couple times. Always a good conversation.

[00:05:14] Jacob Winograd: Always good to, remind people. I was actually just recording a podcast yesterday and in my recording it was plugging those episodes with Bob. I’ll have to link yours when it comes out as well because it’s just, I mean. We’re not here to talk about this stuff tonight, but it’s just, yeah.

[00:05:30] Jacob Winograd: Talking about economics and politics can sometimes, like it’s not I enjoy it to a point, but not as much as I enjoy talking about theology like we’re going to do tonight. But for like your average Christian Evangelical or even just, normal American, like they, they understand how like the economy affects them in terms of like how it hurts their, their bank accounts, right.

[00:05:49] Jacob Winograd: But they don’t always, like, do the connection of like how things like interest rates and monetary policy, don’t just affect how easy it is to get a loan, how it has like this giant trickle effect [00:06:00] over the entire economy to distort how people invest, how people save and really like, to like our Christian nationalist, brothers and sisters who are concerned about, the rise of degeneracy and secularism, if they really cared about that problem and understood it to its fullest.

[00:06:16] Jacob Winograd: They would be the loudest proponents against our monetary policy in federal, in the Federal Reserve. Which to be fair, some of them are but many were ignorant to it.

[00:06:25] Alex Bernardo: Yeah, no, I agree. And the great thing about Bob Murphy in particular is that he is able to talk about these very complex subjects in a way that the average person can understand.

[00:06:33] Alex Bernardo: And he also does so with humor and grace too. A lot of the times, like when people talk about the Federal Reserve, you, I mean, you get mad because of how much it screws the average American over, but he is able to maintain a good sense of humor throughout all of these conversations. I just have a ton of respect for him being able to do that with the amount of knowledge that he has.

[00:06:52] Jacob Winograd: Right on. So. We are gonna talk tonight about something which is almost, you could say, not that we necessarily planned it this way, but like a, it’s almost like a longer overdue part two to like our first ever conversation, which I had you on my old show, the Daniel three podcast. I think it was episode 92, the last, it was like the last regular Daniel three episode.

[00:07:15] Jacob Winograd: I did a, I did like a soft relaunch last year, just for fun. But yeah, I’m just too busy. I can’t keep it going. But we we talked about biblical inerrancy and how to kinda like tonight, like a con, not really a debate, a conversation about how we read the Bible, what these terms mean, how scripture informs us, how we should read it.

[00:07:33] Jacob Winograd: And so we’re gonna, I think, dive a little bit, not like too granular, a little bit more granular that than that conversation. We’re gonna, I think, talk about just the different ways that we read the Bible. And I don’t know that there, the way I’m going to list it out is necessarily like.

[00:07:49] Jacob Winograd: The exhaustive list, like people might define it differently depending on what tradition they come from, but in my mind I think that there’s like a literalist kind of like fundamentalist way of reading the Bible. Or you could almost maybe call this like a liberalist way of reading the Bible, which is I think what people sometimes assume most Christians do where you just, like you, you just take the plain reading of the text in, in English, or a King James version only, there’s different sub variance of this.

[00:08:15] Jacob Winograd: But just that, like what it says is what it says. Don’t overcomplicate it, just follow it. And and I don’t want to necessarily, like, already I’m having a hard time explaining it without being too, I don’t know, like, potentially sounded like I’m condescending towards it. Yes, I get it. Yeah.

[00:08:29] Jacob Winograd: But we’ll keep listing through it. Like there’s, there, there’s certainly gonna be times where I appreciate where the more fundamentalist literalist types are coming from. Even if I don’t agree with that method or at least all the time. Then you have like, maybe like the polar opposite would be like theological liberalism, which is kind of like what your average, like unfortunately, a lot of the mainstream Protestant churches have kind of trended in this direct direction where you don’t really read the Bible as like historically true, or even necessarily theological true. But that you just derive kind of like wisdom and truth from it.

[00:08:58] Jacob Winograd: And there’s varying degrees of that, but it’s it’s very much informed by, less of a, like the opposite of fundamentalism. It’s, it might be the word of God, but like it’s not, whatever the opposite of inerrancy is kind of where theological liberalism is.

[00:09:10] Jacob Winograd: Everything’s optional. Right, exactly. So then there’s different things that, and these don’t, some of these are gonna be like, I think ways of reading the Bible that don’t have to be like. You only do it this way, you can employ different types of reading it. But there is sort of like the redemptive historical reading.

[00:09:26] Jacob Winograd: People will throw out round terms like Christ centric. And then there is of course like I know there’s even, which is related to liberal theology. There’s like political readings of it, like liberation theology. Yeah. There’s, typological readings of the Bible. Then there’s like, and this is I think the most popular in like the reformed camp, which is kind of where I’m more influenced from.

[00:09:45] Jacob Winograd: There’s like systematic theology where now the goal is that hopefully you build your systematic theology by reading the Bible. But it’s also, it’s kinda like a both and like it’s informed by the Bible and systematic theology as supposed to be sort of like a worldview or lens that you sort of read the Bible through.

[00:10:02] Jacob Winograd: So that’s kinda like, I think all the different ways and a brief explanation of them. Do you wanna add anything to that? Like anything you think I missed or any, comments on any of those ways at the onset here in terms of your just initial thoughts on the different ways that different Christian denominations and camps read the Bible?

[00:10:19] Alex Bernardo: No I really do think that is a pretty good summary of the mainstream ways that people read the Bible. I think that the point that I want everyone to keep in mind as we have this conversation night is just how complicated all of these issues are. And Christians have been debating these for millennium.

[00:10:32] Alex Bernardo: I mean, this goes back to the earliest days of the church. You had the school in Antioch and the School of Alexandria, and they had different ways of interpreting the Bible. And a lot of the major theological disagreements were actually founded upon method. And so there are a lot of people that grow up in like one particular faith tradition and just assume that everyone around the world should read the Bible in the way that their faith tradition does.

[00:10:50] Alex Bernardo: But all of these faith traditions come from different historical context, which all read the Bible in slightly different ways. So, my, my whole, I guess my, my. My my the disposition that I try to have when I’m confronted with this is an attitude of humility because I realize that like my reading of the Bible too is not perfect.

[00:11:06] Alex Bernardo: And so I just try to learn as much as I can from all of these various camps and then also make judgment calls about what I think is true and false and helpful and unhelpful in each of these ways of reading the Bible.

[00:11:16] Jacob Winograd: Yeah, I, of course, so I say this a lot about my political convictions because. As much as I’m very convinced of the fact that libertarianism is true, the fact that I was not a libertarian at one point, I was actually like a Democratic socialist, right?

[00:11:31] Jacob Winograd: So it’s like, I know I’ve been wrong before. So, it would be rather presumptive to be like, well, I know I’m right now and there’s no more questions or learning to be had. And the same goes with theology. I was raised in a very weird mixture of different things. It was non-denominational churches, so, it’s kind of just a, theological grab bag.

[00:11:50] Jacob Winograd: I was, it was very influenced by dispensationalism and also like very like charismatic so like speaking in tongues and lots of stuff. So it was very interesting [00:12:00] church upbringing. But I was also. My dad was a missionary, so I was able to attend like African churches and see the way they worship and do things.

[00:12:07] Jacob Winograd: So I had a little bit of a exposure to different ways of doing church, but then I became more reformed later in life. So even though I kind of strongly lean towards the reformed, philosophy and theological worldview, I don’t. Hold that with a closed fist, right? Like I hold basically like the nice scene and the apostle’s creed I hold with a closed fist and everything else.

[00:12:30] Jacob Winograd: I try to be as open fisted as I can, if that makes sense. Right, right.

[00:12:34] Alex Bernardo: Yeah, it does. Well, and my, I know we’ve talked about this before too, but my upbringing is very similar in that I was born and baptized Catholic, and then we did a very short stint in the Methodist church and then wound up for the formative years of my life in the Lutheran church.

[00:12:46] Alex Bernardo: And then I went to like a restoration movement college all where a lot of Baptist attended. And and and then I wound up working at the Lutheran church and in a Methodist church, and now we go to a Nazarene church. So I’ve been all over and I genuinely believe that there are a lot of theological strengths in many of these traditions, and there are good, faithful people that come from all of these backgrounds.

[00:13:03] Alex Bernardo: But I also see areas where it seems like some of the official doctrines of each of these churches. Conflict with what the Bible is actually saying, and that leads me to be a little bit skeptical. It’s not that I think that there’s one tradition That’s right. It’s that I think that there are probably good aspects of all of these traditions, emphases, that we maybe need to think about and incorporate, but then there are also downsides as well.

[00:13:22] Jacob Winograd: Yeah, I think I sort of take a similar approach. Like I, as much as I’m reformed leaning, I try to take a sort of. Ecumenical kind of like mere Christianity approach to these things. And I wholeheartedly agree, like even with denominations that are supposed to be almost the polar opposite of reformed, like Eastern Orthodox is just about as different in terms of, so meteorology and kind of similar in church structure.

[00:13:49] Jacob Winograd: But other than that, like very just different emphasis of how we read scripture of how we cooperate or don’t cooperate with God’s grace. But there are things about the Eastern Orthodox tradition, the way they do worship, the way they do liturgy, the way they view sanctification, that actually bring value, that increase my understanding of the gospel of scripture.

[00:14:08] Jacob Winograd: And that I think, partly because they’re, they hail more from the eastern part of the world. They have certain traditions and ways of looking about things that like we here in the West don’t usually do. And I find that to be useful. Like sometimes here at the West we can be.

[00:14:22] Jacob Winograd: So like, it’s not just a reformed thing. I think you’d agree, even like Catholics and Lutherans to a lesser extent, we categorize everything. We systemize everything. And sometimes like we’re not as quick to like lean into the more like mystic sort of spiritual part of the faith where it’s like, there, there is this sort of like parts of the message of Jesus Christ that, not that we can’t talk about them, but like they’re just so above our heads.

[00:14:49] Jacob Winograd: Like, just so otherworldly that like, if we can, again I don’t wanna like couch everything I said. Like I know, like even like someone like Wayne Gruden who’s wrote like a big book on systematic theology who I read would agree with this, that like, just because we can systematize things and write things down doesn’t mean that then like, okay, we got it figured out.

[00:15:07] Jacob Winograd: Right. Absolutely. But that can sometimes be. A trap that some western Christians of different traditions fall into. And that’s why I think, conversations like this are, I think, aimed at us challenging each other in a way where it’s not about like, who’s right and who’s wrong. More than that.

[00:15:23] Jacob Winograd: More than, it’s like, how can we even, push each other to even to do even better than we are currently doing in pursuing the truth and understanding it more.

[00:15:33] Alex Bernardo: Yeah I agree. And there, there really is no bigger question in the question of God. And I’ve always thought that it’s very arrogant and almost blasphemous in a way to say that an individual can construct a theology that is entirely correct.

[00:15:46] Alex Bernardo: And even the writers of the Bible, I mean, almost all of the language that the biblical writers used to refer to God as anthropomorphic. Because the only like way that we can describe this transcendent reality is by analogy to the physical world. But like we all know, and the writers of the Bible just assume that God is kind of beyond our ability to categorize and describe.

[00:16:05] Alex Bernardo: And so we have to try to get as, as close as possible. And this doesn’t mean that God reveals himself in Jesus. This doesn’t mean we have nothing there and far from it, but it just means that we have to have humility and realize that we are creatures in search of this infinite creator.

[00:16:20] Alex Bernardo: And that, that there’s always going to be a sense in which that’s beyond our ability to reach. Do to language. Like we’re just not going to be able to accurately translate or adequately translate God into our human categories. It’s just not a possibility. And I think that’s a very Okay.

[00:16:35] Alex Bernardo: And actually valuable place to start.

[00:16:37] Jacob Winograd: Yeah. So one of the things, so I framed this discussion as like systematic theology versus like more like, like a historical critical studies. Yeah. Historic scholarship sort of reading and you have, with your biblical studies background, and I know from listening to your show that you talk to a lot of biblical scholars.

[00:16:54] Jacob Winograd: You listen to a lot of, and read a lot of biblical scholarship and. I don’t want to suggest that we as Christians should not be reading scholarship, both like older scholarship or even newer scholarship. Like I get a lot of value from even reading someone like Bart Erman, who is Oh yeah, an agnostic atheist type.

[00:17:13] Jacob Winograd: Even though he is not a Christian and his goal is not to be an apologist for Christianity, there are things from his work and scholarship, which I think actually whether that’s his intention or not actually bolster the case for Christ and the case for Christianity. So, and to also.

[00:17:30] Jacob Winograd: Put another pin on that. If we as Christians aren’t reading modern scholarship, then that means that people, like, part of the people we’re supposed to be doing evangelism to are going to read that scholarship and have questions for us, and we’re not gonna be able to like, give any answers.

[00:17:44] Jacob Winograd: Right. Right. Which I think is just a horrible way of doing Christianity and evangelism and having a witness. And, we’re taught, we’re called to have a defense. And in some ways although we have it better than like Christians throughout most of history who didn’t have the full printed [00:18:00] Bible, at all times at their disposal because of technology or because of, maybe the church, Catholic church not wanting everyone to read the Bible at certain times.

[00:18:08] Jacob Winograd: But like today, although we have the benefit of just the Bible of being able to go online and look at manuscripts and read all sorts of commentaries, it’s also like on the flip side, we have more of a challenge now. Because of all the scholarship and all the challenges that can be raised and, the the historical critical approach when it’s done from a secular viewpoint can present a lot of questions and point poke a lot of supposed holes in the Christian religion that those who don’t know anything can quickly find themselves, at least for a season.

[00:18:39] Jacob Winograd: Sort of like disillusioned in their perception to their faith where they feel like they’ve been lied to. And I think that was like a lot of experience of like Christians and churches and like, the heyday of like the new atheist movement when a lot of this stuff was really popular.

[00:18:52] Alex Bernardo: Yeah, no I completely agree with that. And this is one of the reasons why I think trying to have these conversations is so important. We need to create spaces where Christians feel like they can ask questions and where we can have serious debates and conversations about how to understand all these issues.

[00:19:07] Alex Bernardo: ’cause they are incredibly complicated. One of the things that I experienced when I was in youth ministry was I saw that kids that tended to be raised in homes that did not allow them to ask questions and have kind of the and kind of wrestle with these doubts and and the challenges that they were experiencing, their faith.

[00:19:22] Alex Bernardo: Almost all of those kids tended to abandon their faith when they got older. And I understand why. It’s ’cause they never felt like they had the space to even ask. And so if you grow up in a home where you’re kind of raised in bad theology and then you go to college and you have some, philosophy 1 0 1 professor, just present all of these arguments against God that you’ve never heard before, it’s very easy to get caught up in that.

[00:19:39] Alex Bernardo: So I understand why people,

[00:19:40] Jacob Winograd: yeah. Or it’s easy if you don’t lose your faith to just adopt some kind of theologically liberal view of it. Right? Because you can’t, like, you can no longer at least defend the inspiration of scripture, which is, before I was reformed, I had, I wasn’t like fully theological liberal, but I had like adopted a lot of theologically liberal positions about the Bible and about the gospel and the history of the Bible and things like that.

[00:20:04] Jacob Winograd: And that was because I was raised in a very, kinda like fundamentalist literalist background that like, I wouldn’t say they shamed me for asking these questions, but they just didn’t have answers. Like they just, they didn’t even know how to process the kind of questions I was asking based on just the things I was being challenged on by my peers and listening to on YouTube and reading online.

[00:20:24] Jacob Winograd: So they were just like, they just weren’t ready for it. They weren’t equipped now. Then later on when I actually, I became a libertarian. Then I was in the Anarchical Christian Facebook group and I was like presenting these questions, and there I found people who were like, oh no, there are really good answers for all these questions you have about like, what about the contradictions in the Bible?

[00:20:41] Jacob Winograd: And how do we know that the things that Jesus said or the things that Jesus said and all that, like, here’s all these really good scholarly explanations for these things. Which then, brought me back to, I guess like lowercase orthodoxy. But it doesn’t have to be this hard, we don’t have to have this problem, so the more knowledge we have, the more discussions we have with the church and even like, I would just encourage like pastors and people who are in church leadership and elders, like if someone, one of your laymen or a teenager or someone asks you a question you don’t know, like.

[00:21:09] Jacob Winograd: You like, just be like, Hey, I don’t know, let’s figure that out together. Right, right. Like, let’s go and study it. Like, I’m sure there’s an answer. Let’s go find it, let’s go study. Like encourage people to ask questions and not make it feel like they’re like, like my wife was more recently saved and baptized, and that’s why like, she’ll come and ask me questions and just be like, like, I believe in this, but like, this part doesn’t make sense.

[00:21:31] Jacob Winograd: And like, and then I get like really excited. I’m like, oh, that’s really good question. And then we go on like a, we’ll be up to like 12 o’clock in the morning instead of Netflix and chill. We’re like, like two laptops open, a bunch of commentaries open, just like, yeah.

[00:21:44] Jacob Winograd: Connecting all the dots of things like that. So, that should be like, it should be a joy when people ask us questions. I think. I do think so. So here’s like one of my first, I guess, like more challenging questions. When I approach scripture. I think that I want to have a purchase on like the historical context, right?

[00:22:01] Jacob Winograd: I wanna know who wrote it. I want to know the time period. I want to, I wanna have like, at least a beginning knowledge of like cultural norms and political contexts. I want to be aware of, like if it’s Old Testament, I want to be aware of the challenges of Hebrew. If it’s New Testament, I wanna be aware of the challenges of Greek.

[00:22:19] Jacob Winograd: And I think that something I often hear is that like, well, the, what scripture means is whatever the original author meant when he wrote it, and how like the original audience would receive it. And that sometimes will be juxtaposed with sort of like systematic theology, which I don’t think ignores all that, but I think takes a different approach, partly because I think that, like, for example, there are certainly.

[00:22:50] Jacob Winograd: I think like if you look especially like new to Old Testament, there are times where Jesus and the Apostles are taking Old Testament scripture, like from the Torah, from the prophets, and basically saying like, the way that, at least the way that the original audience understood those passages, like what they meant they were wrong in their understanding.

[00:23:13] Jacob Winograd: Right. And so, so, so what do you think about that? Like, ’cause I think there’s like a bit of a tension there in terms of the, like the scholarship is important, but like, is there ever a case where the author meant something or the audience would’ve understood it as meaning something, but that’s not ultimately the fullness of what was meant that like they missed something.

[00:23:36] Alex Bernardo: Well, I guess, I guess it depends on what you mean by the fullness of what is meant. I mean, I definitely see where you’re coming from with that question. I think to kind of, to frame this maybe in a slightly different way. I we have to understand that all of the texts that are in the Bible are products of particular historical context.

[00:23:52] Alex Bernardo: And so they are going to reflect obviously, the characteristics of that context. And that’s inescapable. And so if you want to have some sort of. [00:24:00] Foundation upon which we can build theology which we have to do. So I’m not denying or marginalizing theology. It’s incredibly important for the church and that’s what gives us the guardrails that we need to stay within the lane that God intends us to.

[00:24:12] Alex Bernardo: So we have to have that kind of theology. But we also have to be aware that, like to take, for example, the letter to the Romans, it’s in, in the very first passage of Paul’s letter to the Romans, he says, as a part of God’s inspired scripture, that he’s writing this to the Romans. And so if we wanna understand exactly what Paul is getting at in that text, then we have to understand a little bit about the Roman context, about the possible ways in which they would’ve heard what Paul was saying.

[00:24:36] Alex Bernardo: We have to try to reconstruct to the best of our ability, the background into which Paul is writing. ’cause we don’t have the, and Paul is communicating with the Romans for the first time, but we don’t know exactly what situation Paul was writing to except for inferences that we get. From the text because we don’t have any communications from the Roman Church to Paul, or we don’t have any conversations that he had about what was going on in Rome.

[00:24:57] Alex Bernardo: And I think the point that I wanna make about the historical context in all of in, in all in, in this situation here, is that we don’t want to build up a system of theology that is completely incompatible with the original context of a given passage in the Bible, right? And so. With history, a lot of these issues are unsettled, then they’ll forever be unsettled because there aren’t any easy answers to these historical questions.

[00:25:22] Alex Bernardo: But if we’re not trying to think how was this text designed to work in its original context, then we don’t have even like a firm foundation from which we can build our theology. And I think that there are a lot of people that want to go straight to constructing that theology. But when you do that without reference to the original intention of the text, then you wind up importing all of your own kind of modern ideas and all of your cultural baggage back into the text, and then you wind up reading your own context back into it instead of letting it speak for itself.

[00:25:48] Alex Bernardo: Now again, like going back to your example the writers of the New Testament do use the Old Testament in very innovative ways. But that’s pretty consistent with the ways that Jews interpreted their scripture. They were much more flexible in their interpretation. And I’m actually, I’m like I’m absolutely fine with like Christian devotional reading of the Bible.

[00:26:04] Alex Bernardo: And I think that’s a good thing. That’s, it’s a good habit to have, but we do have to realize at a certain point that when we’re reading the Bible for like personal edification, we might be reading it in a way that doesn’t necessarily correspond to the original intention of the text. And that doesn’t mean that those two things are necessarily in conflict with one another.

[00:26:20] Alex Bernardo: We just need to make sure that we’re trying our best to respect the fact that these texts have a history and make sure that whatever we’re doing with the Bible in the modern era doesn’t directly contradict that. Does that make sense?

[00:26:31] Jacob Winograd: I think so, and I can draw a couple parallels. Like this isn’t exactly about historical reading, but I often try to be careful whenever I’m using scripture to draw some sort of like, world building or like, like using it to inform a sort of like biblically constructed worldview that I don’t give off the impression that I am.

[00:26:53] Jacob Winograd: Implying the text is sort of like unidimensional. So like, lemme give you an example. Like the the parable of the workers in the vineyard is obviously one of Jesus’s many parables about the kingdom of God, right? And I also think that for that parable to actually work in terms of the lesson it’s giving where like the master is free to give the same payment to all, whether they showed up first or they showed up last.

[00:27:22] Jacob Winograd: And regardless of the work he did, because it’s it, because it, because he’s like, he says, well, this was my property. Am I not free to use it how I please right now, what that’s corollary to is God. Is he just saying that like God. Obviously like made a promise to Abraham, made a promise to the the Hebrews to the Jewish people, but he’s also able to then extend that promise and offer the same thing to the Gentiles.

[00:27:48] Jacob Winograd: And the kingdom of God is not like a, it’s not merit based, but it’s not about if you came first, you came last, or how much work you did. It’s not about even this like human conception of like fairness but it’s about, God’s prerogative in and giving grace and in choosing people to receive that grace.

[00:28:05] Jacob Winograd: And so this is one of the ways in which the kingdom of God is upside down in comparison to how earthly kingdoms and expectations are now for that parable to make sense. There’s like a logical implication from there about property, which I, so I use this, I think it’s Matthew 20 or 21.

[00:28:22] Jacob Winograd: I use this to make an argument about property rights that like the parable would kind of be nonsensical if. Because like obviously the libertarian view is that like property rights are like the maximum, right? Like they’re the ultimate, right? In terms of that. Like if you own it, which, so that what you own, which includes your body, then no one has a right to take it from you or to tell you how to use it as long as you’re not hurting anyone else.

[00:28:47] Jacob Winograd: So I think that an implication of the parable of the workers in the vineyard is this fundamental idea of property and that like, ’cause as the master says, like, is it not my property? Am I not free to use it as I will? It’d be weird to sort of make that point to then demonstrate that kingdom lesson, but that actually like, oh, but like by the way, property is an absolute and you’re not free to do with your property that which you wish.

[00:29:11] Jacob Winograd: Like that would just be a confused read. So that’s an example I think of like where now. I don’t think when Jesus was speaking this parable and the people were hearing this parable, they were like, well, obviously this is about property rights, right? Like, so I don’t want to ever like, give that impression that like, I’m reading libertarianism into the text, or I’m like doing some kind of like, almost like libertarian liberation theology, right?

[00:29:35] Jacob Winograd: Like that’s that which I mean sound, I mean, if you’re gonna do liberation theology, I guess make it libertarian, but, right. Yeah. But that, so I think that’s kind of what you’re getting at is that like we can, so we could probably agree that we can take, sort of like secondary lessons and there’s the potential that, that, like there can be more meaning to a text.

[00:29:54] Jacob Winograd: Or more lessons than the original author and audience might have intended. But we do wanna be [00:30:00] careful that like, if that message were to be contradictory to the historical reading you, you say that there might be a problem there at that point.

[00:30:08] Alex Bernardo: Yeah. Right. And I, again, I don’t think that drawing that conclusion from that text is at odds with the intention of the text.

[00:30:14] Alex Bernardo: Now again, it’s like you were saying, Jesus did not set out when he spoke that parable to explain property rights. It’s parable about the kingdom of God and the right inclusion of tax collectors and other sinners, people that the Jewish elite deemed outside of the circle of those who would be rescued in the coming restoration.

[00:30:29] Alex Bernardo: Right. So it’s about that. However, like a good historical question would be, well, how did Jews in the first century understand property rights? And you can go back to the decalogue and look at the, the last. Five Commandments of the 10 Commandments and think, well, a lot of these really are about the management and respect of other people’s property, and they, that all makes sense for them, that context.

[00:30:47] Alex Bernardo: And so you could say, yeah, as a consequence of reading this, we can draw the conclusion that property rights are something to be respected, right? Knowing that’s not the original intention of the text, but that reading isn’t in conflict with it. A good example of a way that progressive Christians, I think make a mistake with these kinds of texts.

[00:31:03] Alex Bernardo: I’m looking at progressive Christians in particular, here are the passages in Acts chapter two and Acts chapter four about the church in Jerusalem selling all their possessions and giving to one another so that no one was in need. Okay, yeah. That’s absolutely what they did. And that’s radical generosity.

[00:31:18] Alex Bernardo: It’s based on the kingdom of God. You can’t then deduce from that, that we need to give a centralized. Date a monopoly over charity like that is completely incompatible with the original intention of the text. Like radical charity is completely compatible with it. Giving to your neighbors starting a food pantry or some sort of like backpack drive for the people in your community.

[00:31:36] Alex Bernardo: All of that completely compatible outworking of Acts chapter two. Saying that we need authoritarian socialism is not an outworking of that. And that’s a, and that’s a great example of when people aren’t trying to ground their readings of scripture in like historically plausible reconstructions of.

[00:31:51] Alex Bernardo: Text, they wind up making these kind of like modernizing claims on the text that are completely at odds with what the original authors were trying to communicate. ’cause again, like a, a great example of this is that at my church, we have a very thriving food pantry. And the guy that’s founded it at our church did it because he believed that the Bible told him that we needed to be charitable and help our community.

[00:32:13] Alex Bernardo: And we do great work. And so I could easily look at a passage like Acts two and say, look, here’s an example of where this happened in the New Testament, and we’re just trying to be faithful and live that out in the modern world that wouldn’t be compatible, even though Acts chapter two isn’t telling us to start a food pantry and my city.

[00:32:27] Alex Bernardo: Right. So that’s the idea that I’m getting at there. We need to think about when we are using the text in ways that it wasn’t originally intended to do, we need to make sure that we’re doing that in a way that doesn’t contradict the original intentions of the authors.

[00:32:39] Jacob Winograd: Right. So let me ex, let me give you a little bit of a ramp up to this next, sort of like challenge or question.

[00:32:46] Jacob Winograd: So. I deal a lot because of my Jewish background and I have Jewish family. I even have a father who used to be, he was Jewish and then he was Christian. Now he’s Jewish again. Yeah. But dude, have

[00:32:59] Alex Bernardo: you been to Israel though? Like, have you actually been there? No.

[00:33:01] Jacob Winograd: No,

[00:33:01] Alex Bernardo: I

[00:33:02] Jacob Winograd: guess

[00:33:02] Alex Bernardo: not.

[00:33:04] Jacob Winograd: Oh boy. Anyways, yeah, I hear you.

[00:33:06] Jacob Winograd: No, that’s a good one. So I am often I spend a lot of time listening and reading the different, like Jewish arguments against the case for Jesus as Messiah. And so, like part of my concern is that actually a lot of what they say is arguments that sound, they kind of mere yours where they say, well, the New Testament authors and the Christian Church took a lot of Old Testament passages and ripped them from their historical context and reinterpret them in ways that like, even if there was.

[00:33:40] Jacob Winograd: And they, the Jewish tradition documents a lot of the, like different interpretations for different things, but like there were for a lot of what different ways the New Testament authors reinterpreted the Old Testament, including, like things they said, Jesus said they weren’t things that were at all, or at least they, if they were, we don’t have any evidence of it, at the very least.

[00:34:02] Jacob Winograd: Things that, like the original riders or receivers of that, or even, hundreds of years later in Jesus at the time, were really thinking, like, oh, this is a, so like, give you an example. One of the. The first, like, this was supposed to be like the, this was supposed to, like, the first time I was like given to it.

[00:34:21] Jacob Winograd: It was like, this is gonna make you abandon your faith in Jesus, like immediately. Right. I was told that, Matthew is a liar that he in Matthew two when the family flees to Egypt and it says this was the fulfilled prophecy out of Egypt. I called my son. They’re like, well, that’s quoting Hosea 11, which has nothing to do with the Messiah.

[00:34:42] Jacob Winograd: This is just, a retelling of Israel’s history. And so, Matthew is just like, an absolute crank. Right. And they’re just like, Jesus doesn’t fulfill all these other prophecies. And then they had to like, invent new prophecies to try to say Jesus fulfilled them to try to bolster his case to be Messiah.

[00:34:59] Jacob Winograd: Well then I did, I’d never really like, read that passage as much thought. So then I went back and Rew went through and read Hosea like, cover to cover and. Jose 11 through 13 are almost like one section because it is kind of like God recounting his history with Israel and he starts with the like, Israel with like a son who I loved out of Egypt.

[00:35:18] Jacob Winograd: I called my son and recounts the history. Then you get like Hosea 13 and it’s like, God, like rebuking them and just a little quick libertarian pivot hearkening back to first Samuel eight, where he is like, you guys asked for a king, right? And I gave you a king in my anger. So like, I always love when people try to say that, like, if you try to reinterpret first Samuel eight to say that God didn’t give them the king in anger, it’s just like, okay, then you gotta deal with the Hosea passage, right?

[00:35:42] Jacob Winograd: Which reaffirms that, like the whole king thing was a bad idea anyway. So yeah, there’s nothing in there explicitly about a Messiah, but the point Matthew is making, which is then like. Very evident when you go and read Romans, when you read Galatians, when you read Hebrews, is not that [00:36:00] these passages were actually initially about Jesus or about the Messiah, but that the Messiah in Jesus is the fulfillment of Israel.

[00:36:10] Jacob Winograd: That the original mission, the original promises given to Abraham, that then were passed down to Jacob and his sons and the nation of Israel that was formed from that, that as was said in the other prophets and Jeremiah and Isaiah that even in Ezekiel that like you have, not kept up the covenant and there’s a need for a new covenant.

[00:36:29] Jacob Winograd: One where the law isn’t something you wear, but something that’s in your heart, something the heart of stone is substituted for the heart of flesh and. So, so Jesus is that fulfillment is that new covenant. And he is the successor to Israel. He’s the true Israel in a sense that he goes through. And the point Matthew’s making is that by hearkening back to Hosea 11 through 13, is that Jesus is going on the same, basically like both typological and almost geographical journey of, being called into exiled to Egypt, called out of it and then called to this specific mission, right, to be like a royal priesthood, a blessing to the nations.

[00:37:10] Jacob Winograd: And Jesus succeeds where Israel fails. That’s like, that’s what Matthew is setting up in chapter two. And that is such like a deep point, but like no one reading Jose 11, 13. The time it was written or even in the year of Jesus was reading this, going like, man, I really think that there’s gonna be a Messiah figure who comes up and he’s going to like that.

[00:37:33] Jacob Winograd: That kind of reading of that text was just not in their minds at all, nor do I even think we can know if it was in the prophet’s mind when he was ri writing those words down and delivering them. Right. So that’s where I get a little, I guess, like worried about this historic approach. Not that I think we dismiss it entirely, but I think it’s one of at least several examples, which I think there’s a lot of examples where I think we have evidence that there are times where we are gonna read the especially the Old Testament.

[00:38:08] Jacob Winograd: The New Testament, I think is a bit more nuanced, but I think there could be times where we read the Old Testament and. True things. Maybe even the correct reading of those certain texts is going to be radically different than what the original authors intended. Or at least like, we can speculate, like maybe they knew in the back of their heads, maybe like they had, more revelation as they, like I know, like, Yeah,

[00:38:30] Alex Bernardo: I’m with you.

[00:38:30] Alex Bernardo: Yeah.

[00:38:31] Jacob Winograd: I mean, there’s some arguments he made that, like David perhaps in his like later years was like able to like see some kind of glimpse that there’s, gonna be a king greater than him and he wasn’t exactly referring to hi his son Solomon and things like that. So, but like, it’s, it is what Hebrew said, right?

[00:38:45] Jacob Winograd: Like they, they had this future hope, but it wasn’t clear, right? But they had faith despite having this very obscure, very like unseen hope, but they just knew that like, that God was going to work something out and not like abandon his people. So, so yeah, that, I think that’s kind of what I’m getting at.

[00:39:03] Jacob Winograd: Like, I think there can be cases where. The right reading of a scripture isn’t what the author or the audience of the time would’ve understood those passages to mean. Now on the flip side, I can see the danger in like, getting carried away with that. Where now we treat the Bible like everyone treats the Constitution today, where it’s a living, breathing document and you can just be like, well, we can just like, reinterpret anything to mean anything we want.

[00:39:28] Jacob Winograd: Because like, we don’t have to appeal to the original meaning of the text and Right. The original. So like, I think there’s this tension here that, so like, to allude to what you said, we don’t have absolute knowledge and so are we ever gonna get like perfect answers on this? No. But I don’t think that means that’s wrong.

[00:39:47] Jacob Winograd: It just means that it makes our job a little bit harder perhaps. But all the more reason to to pursue it faithfully, I guess. So anyway, there’s a lot there, but I think that was important to explain why I, to map out like my personal, I guess, like, stake in this as well as the example of where I think some of these readings can be a little bit difficult if you put too much emphasis on the historical approach.

[00:40:08] Alex Bernardo: Yeah. No I definitely understand that and appreciate some of the difficulties that you’ve highlighted there. I do think that the writers of the New Testament certainly have a christological reading of the old, but again, going back to trying to understand how like prophecy worked in its historical context, there are a lot of people that assume that prophecy means prediction, which doesn’t really prophets like in Israel, they’re primarily designed to be spokespersons for God.

[00:40:32] Alex Bernardo: They’re kind of the intermediary between particularly people in power and God and their whole job is to make sure that those that are in power held accountable to following God’s law. And this was the calling of Isaiah, Ezekiel, Jeremiah. And so their primary function was not to predict the future, but to hold the people of Israel accountable to the covenant that God had made with them in the present.

[00:40:52] Alex Bernardo: Now, insofar as they did that, they’re reading passages like Deuteronomy 30, which look at, which kind of explore the idea that Israel is going to transgress the covenant, therefore God is going to curse them. But when. The time of cursing is over. God is going to restore Israel. So they look back to passages like that, and they struggle to come up with language to describe how great that coming restoration is going to be.

[00:41:14] Alex Bernardo: And so, like the prophecies in the Old Testament are not designed to be extremely precise predictions of what’s going to happen in the future. They are kind of general reassurances to those that are faithful in Israel, that God is going to make everything right despite the fact that they’re having to deal with all of these problems because of Israel’s general unfaithfulness in the present.

[00:41:33] Alex Bernardo: And so when you, and this is really where like the development of apocalyptic language comes from. If you take a look at a passage like Joel chapter two, for instance, where, and this becomes a very common apocalyptic motif in Jewish writings, but in Joel chapter two, he talks about the, like, the time of restoration when God comes back and rescues Israel from.

[00:41:51] Alex Bernardo: There are sins, and he talks about how the stars are gonna fall out of the sky and the moon will become blood, and there’s going to be this giant cosmic cataclysm. Joel doesn’t mean that [00:42:00] those things are literally going to happen. He just doesn’t have any language to describe how much of a transformation it will be for the cosmos when God finally comes back to restore Israel.

[00:42:08] Alex Bernardo: And so he has to appeal to that kind of language. And so when you get to Jesus, and you can look at this, when you read the passion narratives and the gospels in particular, no one like no one in Second Temple Judaism had any idea that when the Davidic Messiah came, he was going to have to be crucified.

[00:42:22] Alex Bernardo: They had no clue that was what it was going to. Be like, but then once Jesus was raised from the dead, his followers went back and reread the scriptures and thought like, okay, well if you look at this directionally, it was kind of pointed towards this all along. There was no other way this could be.

[00:42:35] Alex Bernardo: And the other thing that the writers of the New Testament do and the work Richard Hayes was one of the, and I know Richard Hayes had some very progressive political positions at the end of his career, but his scholarship was genuinely are generally very good. But he’s very popular for doing a lot of work on the way that writers of the New Testament utilize the old.

[00:42:52] Alex Bernardo: And one of the points that he makes over and over again, which is true in passage after passage is that when writers of the New Testament are quoting directly from the old, they almost always have the entire context of the original passage in mind. So a great example of that is what you’ve already brought up the quotation from Hosea 11 one in Matthew chapter two.

[00:43:09] Alex Bernardo: So if you look at that, it’s not directly predicting the birth of Jesus or Jesus’ family going to Israel and coming out the other side. It’s a passage about God delivering Israel. Israel being unfaithful, and then God restoring them. And so what Matthew is doing by utilizing that passage is he saying that restoration that Hosea was pointing towards, this is happening with Jesus.

[00:43:29] Alex Bernardo: And so it becomes kind of like a typological pre figuration of what’s currently going on with Christ. And this is not to say that Hosea intended for that text to be used that way, but going back to what I was saying before, it’s not inconsistent with the larger message of Hosea. Another really good example of this comes from the passion narratives, at least in Mark and Matthew.

[00:43:49] Alex Bernardo: Luke and John use a different reference here, but the final words that Jesus says before he dies and the Gospel of Mark and the gospel of Matthew are actually a quotation of Psalm 22, 1. My God, why have you forsaken me? And there have been, thousands and thousands of pages written speculating what Jesus meant by that.

[00:44:05] Alex Bernardo: But if you read Psalm 22 in context, it’s about the like a suffering Davidic figure who is eventually restored and exalted by God, which is exactly what happens when Jesus is raised from the dead. So you can kind of see that very brilliant way that these writers of the New Testament are looking back at these passages in the Old Testament, taking the entire context into account and then using this to creatively construct a narrative about.

[00:44:27] Alex Bernardo: Jesus. And all of this would’ve been completely acceptable within the boundaries of first century Greco-Roman biography, which is the genre in which the gospels were written. Another very important historical point that people don’t often consider. ’cause it’s very easy to look at, like, for instance, the discrepancies between the stories in Mark, Matthew, and Luke and say, well, obviously the Bible is contradicting itself because they’re telling the same story in different ways.

[00:44:50] Alex Bernardo: But this is exactly what you would expect from ancient biographies that were based on oral tradition. These were kind of the rules within which the ancients operated. No one would’ve seen a pro, like no one would’ve seen a problem with that in antiquity in the way that we do in the modern world. So I think kind of keeping these ideas in our head as we read through these passages in the Bible, allows us to see how these the writers were using this strategically.

[00:45:12] Alex Bernardo: Does that make a little bit of sense? To answer your question, there was a lot that I wanna make sure I cover all of it, but that was kind of one Yeah. Aspect of it.

[00:45:17] Jacob Winograd: I think so. Let me see if I can. Restate some of those things in my own words to make sure I was tracking it. I think part of what you’re saying is that there’s perhaps a distinction to be made in when we’re reading things that are prophecy versus other teachings.

[00:45:33] Jacob Winograd: Because prophecy by its very nature, should never have been understood even and think maybe certain Jews at the time or later on in Jesus’ time were incorrect at certain points and then making a false assumption that, oh, now we need to be reading these prophecies and expecting them to be fulfilled in a more, literalist sense.

[00:45:53] Jacob Winograd: But that in general prophecy was generally not always expected to be like a, well, this is a one for one prediction. Some of them might be prediction, some of ’em might be warnings, some of them might be, correction or sort of like typological, like not prediction of literal events, but more like, sometimes I, I think certain passages are not even, this is, I guess my own somewhat inform formed by my millennial perspective, but I think sometimes, like certain eschatological passages are not even like a warning of a specific event, but like, sort of like laying out like a certain pattern that can happen if certain, like, prerequisites are met.

[00:46:30] Jacob Winograd: Right. I mean, it’s kinda like what we see almost like with a, like, even though it was unique in a covenantal sense, that Israel would go through periods of like, unfaithfulness and then they’d be punished and they’d re pet and be restored. Like, okay. Like that does have some map onto like human experience that like we can experience that in our own lives.

[00:46:49] Jacob Winograd: Right. You could say maybe there’s been periods of time where the church has kind of undergone spiritual forms of this. Right. And so I think I see what you’re saying there. I don’t know that, ’cause like, there’s even instances I can think of, like, which, and I have to be careful on how I say this.

[00:47:06] Jacob Winograd: ’cause like I could say with like the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus isn’t necessarily like completely undermining or changing the old covenant law in those instances. Sometimes he’s correcting oral tradition, sometimes he’s correcting the way people have misapplied the law. But he does seem to be at least challenging somewhat of a at least the way the people at the time thought that they were supposed to correctly interpret these passages.

[00:47:34] Jacob Winograd: I think a lot of this, I want you to respond to what I just said, but I think kind of a lot of this is kind of like the underlying problem here is kind of the postmodern dilemma of just like, how do we handle the problem of multiple interpretations of texts? And I guess my answer to that is that.

[00:47:53] Jacob Winograd: We don’t ever have absolute certainty of the right way in necessarily Ev every case, [00:48:00] but we can, if we’re, if we do our homework, we can kind of construct a hierarchy of more or less plausible explanations. And then like if you rank order them, you’ll generally find that only like a handful if more than one, kind of like separate from the rest as, and I think this is kind of what systematic theology is when it’s done right.

[00:48:24] Jacob Winograd: It’s doing that homework, coming up with all the possible answers, and then not just doing that for like one specific text, but then doing that with all the texts and being like, well, is if I have like two possible interpretations of one passage. Okay now like, let me apply those different interpretations and see how those comport with the rest of my understanding of scripture so far.

[00:48:48] Jacob Winograd: And if one of them seems to be in conflict, maybe that leans more credence to the other interpretation being correct. So do you think there’s a value there, or do you think that falls more into being like, there’s too much of a danger of just pushing your own theological preferences into the text at that point?

[00:49:05] Alex Bernardo: Yeah, no I actually I wanna I wanna know, I see someone in the comment post, Andrew Woodall posted that both are important in their own sense, and I would completely agree with that. You have to have both them. I also see that my, my friend Zach said, take the Eucharist. I love that. So, hi Zach. I’m glad you’re here, man.

[00:49:19] Alex Bernardo: He’s a good dude. I had him on the podcast for a great guy, but but yeah, no, I mean, we, we have to have theology. And this is where I think like a lot of these debates come into play. I think that the, you’re right to bring up the postmodern dilemma and. But I do feel like, for me, the greatest inside of the Postmodernist, and I’m most familiar with with Fuco and Leotard, those were the two that were I think, the most influential in my philosophical development.

[00:49:42] Alex Bernardo: Fuko himself did not reject the concept of truth. What Fuco rejected was our ability as human beings to perfectly apprehend it. Since we’re all kind of like subjective and in cultured. Beings, we’re always gonna be bringing our own baggage with us into the text as we interpret it. And then we wind up reading our own experiences in the text.

[00:50:02] Alex Bernardo: And for us as Protestants, if we believe that the Bible should be the sole source of authority or the primary source of authority for faith and doctrine, then it’s a really big problem if we’re using the Bible just to justify our own beliefs. And so that’s what we’re trying to avoid. And I think that by taking it as kind of an.

[00:50:18] Alex Bernardo: By starting with the ario assumption that the Bible is the product of a historical context, and that God intended it to be written within those historical context that allows us to stand back and say, okay, these people, thousands of years ago, they didn’t think like modern Westerners, they didn’t have the same thought categories.

[00:50:35] Alex Bernardo: They didn’t speak the same language. So we know that there’s going to be a little bit of a gap there that allows us to say, well, let’s try to figure out what these, let’s try to figure out what they were saying, and then we can work to build our theology upon that. But I think the point that you were making about like, we have to draw theological conclusions and then we do have to make value judgments about whether or not we think that those theological conclusions correspond with what we see in the rest of scripture.

[00:50:58] Alex Bernardo: And a lot of the times it’s a matter and this is I think very true for me, the older I get, a lot of the times it’s not a matter of me seeing one side of an argument as being entirely correct and another side of an argument is being incorrect. It’s like, well, I see the points that, that this can’t.

[00:51:14] Alex Bernardo: Is making. And I think some of these points are legitimate, but I also see that the points that this other camp is making, and I think that some of the points that they’re making is legitimate and you have to try to find your way through and come to some sort of mediating i, I guess, conclusion based on that.

[00:51:26] Alex Bernardo: Yeah. And some of that might just be my skepticism, but like, the thing about systematic theology in particular, which I do think that we need systematics to a certain degree, is that I went to a restoration movement college, so that’s Church of Christ School not reformed in any way at all.

[00:51:39] Alex Bernardo: And there was, I guess the kind of a, and I’m not, he’s probably not even still alive because he was quite old when I was there. But I think the preeminent systematic theologian for the restoration movement tradition was a guy named Jack Trell and he had a, he had a systematic theology.

[00:51:53] Alex Bernardo: It was like 800 pages long, called The Faith Once for All, and I only met the guy like twice. But I’m pretty sure that he believed that everything that he wrote in that book was like, was true. Like he did not believe that he was an error at all. And I’ve seen that in some of the works of other systematic theologians as well.

[00:52:09] Alex Bernardo: It’s almost this sense that like, okay, so we can kind of patch together all of these different passages from the Bible and come up with a systematic theology that explains everything. Now, most systematic theologies have a lot more, or most systematic theologians have a lot more humility than that.

[00:52:22] Alex Bernardo: But there is that temptation to say, we’ve constructed this tradition and now this tradition can’t be challenged. ’cause this tradition is an accurate reflection of what the Bible says. Whereas like, when you start looking at the Bible from a more historical angle, then you can see, well, maybe there are some aspects of that tradition that correspond to that really well.

[00:52:38] Alex Bernardo: But then maybe there are some other aspects that the Bible tends to challenge. And I just always wanna make sure that we start with the Bible and build up from that instead of taking our theology and then trying to read the Bible in light of that. Now again I’m guilty of this just like everyone is we’re all guilty of reading our own subjective preferences in the text.

[00:52:55] Alex Bernardo: I know that I do it, I change my opinion on many issues. Because I, ’cause I realized, oh, this is just something that, like I believed it’s not something that’s actually found in scripture. So there’s kind of like a dialogical process going on there. But that’s the kind of work that we have to be done.

[00:53:08] Alex Bernardo: I think that what God honors is. I think God honors those who humbly seek him, right? So we don’t have to have settled answers for all of these questions to be secure in our faith. Like we’re justified by faith, not by having the right reading of the Bible or the right systematic theology or understanding, like all the historical methodologies that go into reading the text in his historical context we’re saved by faith.

[00:53:30] Alex Bernardo: And I think that’s really important. But that should also encourage us to have more of these conversations and be more open to people from other traditions. And so for me, yeah, I go to a Nazarene church, and so it’s broadly a part of the Wesleyan tradition. I have problems with certain aspects of Wesleyan theology, but I feel like I can I feel like I’m kind of a, at home there, at least in, in the way that they’re open about having these conversations.

[00:53:49] Alex Bernardo: When I have discussions like with people like you, people that come from different traditions, I’m more interested in learning why they think what they do than in trying to convince them that I’m right, which is probably not gonna happen. And I think that’s maybe a better [00:54:00] starting point for for Christians.

[00:54:01] Alex Bernardo: Does any of that make sense?

[00:54:04] Jacob Winograd: Yeah I think. I often, even if I disagree I think what you said is something I do too, where there’s oftentimes even where I might disagree with someone’s interpretation, it’s not even always that I think that there’s nothing of value there, that they’ve got it totally wrong.

[00:54:20] Jacob Winograd: But it can be a matter of emphasis and a matter of I think sometimes like we can like, like, let give you an example a completely easy passage that no one debates ribbons. 13, I knew it had to come up at some point, right? Yeah. So, I. Don’t agree with like, the interpretation that I think that Cody has, that I know, like Steven Rose of the Anarchy Christian podcast has both guys that I love, but they have the, which I think Norm has this to a point to, because he’s Church of Christ.

[00:54:54] Jacob Winograd: He, they’re informed by the David Lipscomb reading of it, which comes from his work on civil governance. And it basically, I’m gonna like, I’m gonna give for time’s sake, just like my own rendition of it. I’m not doing it fully full justice here, but I’m trying to be fair.

[00:55:10] Jacob Winograd: Stephen often puts it this way that Romans 12 is about the church and Romans 13, at least, like the first half of it is about government. And the point that Paul is making is that these things are not compatible because one is told to not take vengeance to, to bless those who persecute you. That vengeance belongs to God.

[00:55:27] Jacob Winograd: And then Romans 13 describes an institution that’s administering vengeance. That’s, you know that’s not leaving that to God. That in a sense, what Paul’s point, the point that Paul is making is that we submit to these institutions, not because they’re good, but because God uses them as a means of delivering his vengeance on earth in like in this church age, while we’re waiting for the full combination of the kingdom, but that Christians ultimately, like, we’re called to a different ethic.

[00:55:55] Jacob Winograd: We don’t operate by the world’s ethic. We shouldn’t. Really be in civil governance. We’re, but we should like, submit to them more in the sense that like, we’re kind of supposed to live quiet lives and not like, not go to the spart against route, so to speak in, in terms of how we deal with unjust kingdoms or illegitimate rulers.

[00:56:13] Jacob Winograd: So that’s kind of like a summary view of it. I don’t even necessarily, like I would nitpick with certain things there and say I disagree with it. There’s a, there’s an element to it, which I agree with because it’s similar to my interpretation of one Peter two. The honor of the Emperor passage, because I think the lesson of that passage is more that you are going to, like, we all hate Rome, but we’re going to.

[00:56:35] Jacob Winograd: The proper order is to fear God and honor the emperor. And something he says there is that your good conduct is supposed to put the shame, those who do you know, evil to you, right? That when you respond in good, it puts some to shame. So the idea there is that like in, in the face of persecution, whether that’s from a random evil person or from the Roman Empire, we overcome that, not by might, but by, a sort of like, Christ-like model, right?

[00:57:01] Jacob Winograd: I don’t think that’s what Romans 13 is saying though. Like, ’cause I just don’t see I think that is like, like it’s not even, I don’t see it in the text at all. Like, like not even just a surface level reading. Like I just don’t see, like to me that’s almost like you, you are doing a lot of. For lack of a, I mean, it sounds condescending, but it seems like a lot of mental gymnastics to like, Paul is saying this, but like really there, he’s saying this other thing like five layers deeper under the text.

[00:57:27] Jacob Winograd: Whereas it seems to me, the reading I take is that Paul is describing the Office of Civil Justice after he had taught, told Christians to not overcome evil with evil, overcome evil with good vengeance belongs to God. So don’t repay evil for evil. I think the teaching is more Romans 12. It ends with Paul saying, don’t take revenge, don’t like take matters into your own hands.

[00:57:50] Jacob Winograd: Like you you cannot do what God does, which is to bring. Divine exact justice to all wrongdoings that belongs to God, but then follows that up in classic Paul style when he anticipates that, like, people might have questions about what he’s saying by saying like, now we do have governing authorities who wield the sword as God’s minister against those who do evil.

[00:58:11] Jacob Winograd: And that’s an important role. And we should, submit to those that, that, that of course would be with the implication that they’re doing their actual job. Right, right. Like I think the, now my reading I think my reading of Romans 13 and which I get, kind of from Greg and Kerry is not and they would agree with this because I’ve talked to ’em, talked to them about this, that we’re not saying that our reading is everything that was in Paul’s mind, but it’s more like these are logical.

[00:58:36] Jacob Winograd: Implications that come from reading Paul’s words. Like Paul was not imagining stateless civil governance when he wrote Romans 13, but his principle is that it’s a prescriptive office, that it is supposed to do these things. And it, he would not say that like, the, if you have a governing authority, which is not doing what Rodman 13 describes, if it’s being a tear to good works and defending evil, that’s just not a legitimate instance of a governing authority that Rods 13 is describing.

[00:59:06] Jacob Winograd: So it’s not one that we’re called to submit to. So those are two example, I think an example what we’re getting at where like there’s multiple interpretations of a passage of scripture and I don’t know that they’re inha. Like I can get value from like the David Lipscomb reading and I’m not gonna like reject it outright because it does map onto my reading of biblical principles I find elsewhere.

[00:59:27] Jacob Winograd: But I think there like. I wonder where you fall there, because I dunno if you would agree with me that I think the David Lipscomb reading, is it’s I don’t know if it’s a systematic theology reading, but it’s just it’s, to me, it’s not a historic reading. Like, I don’t know how you could read like you almost, you’d almost have to, you.

[00:59:45] Jacob Winograd: Have like a claim to like hidden knowledge of like Paul’s internal thoughts to be like getting that from that text. At least that’s my opinion. I don’t know what your thoughts are on that.

[00:59:54] Alex Bernardo: Yeah. Well, I’m gonna give I’m going to give due credit to my friend Kevin Burr. He’s a, he’s been on my show several times before and I’ve been on [01:00:00] his, he has a podcast called Faith in the Folds.

[01:00:02] Alex Bernardo: He’s a biblical scholar who is a part of the restoration movement tradition. So a big church Christ guy. And on his podcast just a couple of episodes ago, he did an episode on David Lipscomb and his work. ’cause Kevin Burr’s kinda like a closet libertarian, I guess he’s not even really a closet libertarian.

[01:00:16] Alex Bernardo: I’m pretty sure I can say I’m pretty sure I can out him here on the show. But the only engagement that I’ve ever had with Lipscomb work was through that podcast. So I don’t wanna speak to it because I’m not as familiar with it as as you are. But I did get the sense from talking to Kevin Burr about Lipscomb that he would’ve shared the same concerns that you and Greg and Kerry do about.

[01:00:34] Alex Bernardo: Trying to make sure that your understanding of Romans 13, even if again, you’re constructing, a system of theology that isn’t implicit in the text, I think that you are all concerned about making sure that it’s not contradicting it, right? So even though you might disagree about ultimately what Romans 13 means, you both are coming from the starting point that you’re trying to respect the text and not do injustice to it.

[01:00:55] Alex Bernardo: And I think that’s the attitude, the disposition that Christians should have when they’re trying to build theology. We wanna make sure that we’re being respectful, the biblical text, and we also wanna be open to the fact that our systems of theology can be critiqued and modified.

[01:01:09] Alex Bernardo: We come to the conclusion the text is actually doing something else. I think that’s a, that’s a much better starting place to begin with. And again, just and just not that we want to turn, make this new ne Romans 13, but just as like a hi. Just one of these historical insights that I don’t think people consider enough is that the, like the textual apparatus, so the chapter and verse divisions were not added to the Bible until the Middle Ages, right?

[01:01:31] Alex Bernardo: So we’re talking like, for the first thousand years of church history, there was no division between Romans 12 and Romans 13 because Romans 12 and 13 didn’t exist. Right? Like that is just an artificial, it’s very helpful. Full, but it’s like an artificial tool that we’ve imposed upon the text to help us organize it.

[01:01:45] Alex Bernardo: It’s not intrinsic in any way. Yeah. So just because we see like a chapter transition in the New Testament doesn’t mean that the author is transitioning the idea. And this is where like, again, taking the context of the letter as a whole, what is Paul trying to achieve by writing that letter and then the immediate re rhetorical context, which I agree.

[01:02:02] Alex Bernardo: I think that the rhetorical context of Romans 13 actually begins in verses 12, one and two, when Paul talks about, not being conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind so you can offer your bodies a sacrifice to God. And then he spends two chapters explaining to the Romans what that looks like.

[01:02:17] Alex Bernardo: And then at the very beginning of what we call chapter 14, now, he has that conjunction now where it indicates, ’cause Paul does this, especially in First Corinthians, quite often when he’s shifting gears, he’ll introduce a new topic by saying now or now concerning. It does seem like Paul is shifting gears moving to something else.